A new analysis of 29 modified human bones from prehistoric sites in southern Texas shows that ancient people intentionally altered the remains, offering rare insight into their spiritual and cultural practices.

The study, led by Dr. Matthew S. Taylor and published in the Journal of Osteoarchaeology, found that most of the bones came from arms and legs and showed clear cut marks.

The flesh had been removed, and the bones were later broken using a groove-and-snap method—a technique that involves cutting a deep line into the bone before snapping it.

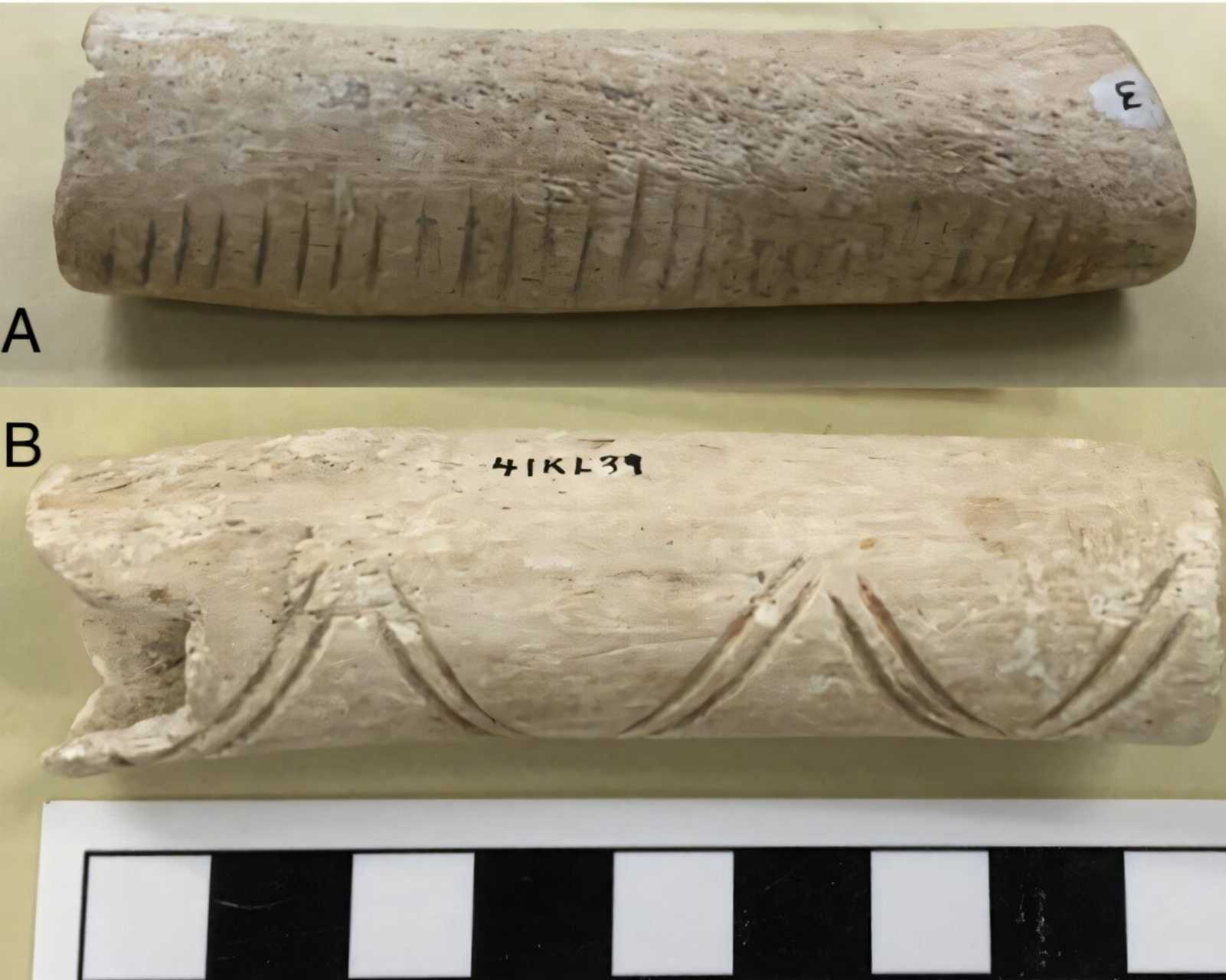

One bone, a left upper arm, had been turned into a musical rasp, similar to those found in ancient Mexico. Carved with 29 notches and a zigzag pattern, it likely produced sound when scraped and may reflect cultural influence from post-Classic Mexican civilizations.

Taylor stated that the modifications might indicate ancestor worship, ritual activity, or the display of war trophies—practices observed in other Native American cultures but rarely documented in South Texas.

“If nothing else, the human bone artifacts act as confirmation that early peoples on the Gulf Coast did not view human bodies, or the reduction of human remains, as taboo or off-limits,” Taylor said.

The bones were examined at the Texas Archaeological Research Laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin. They were originally found at several prehistoric sites in South Texas and had previously gone mostly unstudied, despite brief mentions in 1932 and 1969.

Taylor’s research followed federal requirements under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. The scientists consulted with the Comanche Nation, Caddo Nation, Mescalero Tribe, and Kiowa Tribe. None of the tribes claimed the remains, so the study was cleared to proceed.

While similar bone treatment has been documented in other regions of the Americas, South Texas has seen little detailed bioarchaeological research. Historical records offer limited clues.

Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, shipwrecked on the Gulf Coast in 1528, noted that some tribal members cremated the bones of holy men and drank the ashes in water, possibly a form of ancestor veneration.

Other nearby tribes practiced scalping and kept body parts as war trophies, but no direct evidence links those customs to the southern Texas coast.

Taylor suggests that the musical rasp may reflect cultural exchange with Mesoamerican societies. He refers to the Gilmore Corridor, a proposed trade route along the Gulf Coast that may have connected Mexico to the American Southeast.

However, he noted differences in construction: the southern Texas rasp was made from an arm bone, while Mexican versions were often crafted from thigh bones.

Taylor, who has studied the region’s bioarchaeology for much of his career, said the findings offer a glimpse into how early Gulf Coast communities viewed the body, death, and identity. He explained that these remains help us understand how ancient people lived and how they remembered the dead.