One of humanity’s defining features is the ability to speak in complex languages. Today, nearly 7,000 languages are spoken worldwide and are grouped into about 140 families. The five largest language families are Indo-European, Sino-Tibetan, Niger-Congo, Afro-Asiatic, and Austronesian, which are spoken by enormous swaths of Earth’s population. The Indo-European family is the largest, especially when counting second-language speakers.

It spans 12 branches with historic roots stretching from northwestern China to Western Europe. According to science writer Laura Spinney’s book Proto, half of the world’s population speaks an Indo-European language.

She and archaeologist James Mallory, author of The Indo-Europeans Rediscovered, both examine the origins of this vast language group. Linguist Lorna Gibb offers a broader perspective in Rare Tongues, focusing on endangered and extinct languages.

For centuries, scholars have searched for the original homeland of the Indo-European languages. Mallory documents 176 individuals who proposed possible birthplaces between 1686 and 2024, ranging from the Arctic to the Pacific, and even outside Earth’s galaxy. The theories range from rigorous to absurd.

British judge William Jones is widely credited with identifying early linguistic connections. In 1786, he observed striking similarities between Sanskrit, Latin, and Greek, such as the word for “mother” (mata, mater) and “to fly” (pátami, petō).

He proposed a now-lost common source language, later named Indo-European by physicist Thomas Young in 1813.

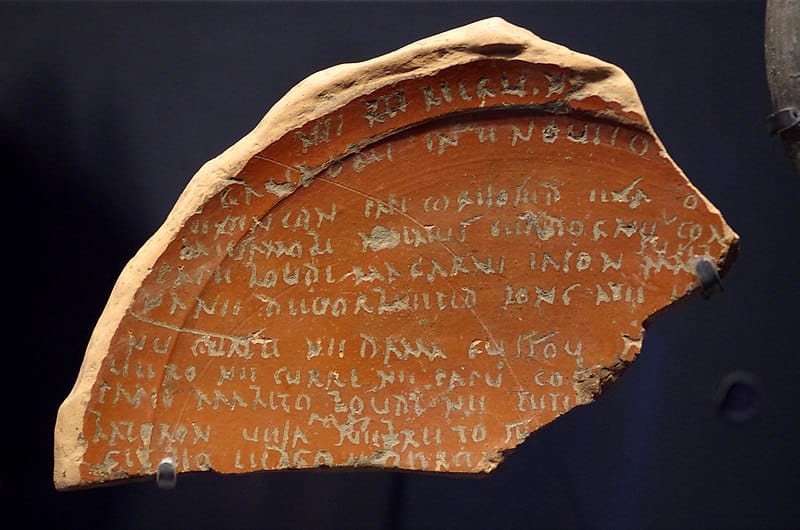

Young placed the homeland in Central Asia, specifically Kashmir. Some scholars later pointed to the Indus Valley civilization, dating back to 3300 B.C., as potential evidence for an “out-of-India” theory. But the region’s undeciphered script offers no reliable proof, and most experts now reject that idea.

By the mid-20th century, theories shifted toward Europe. Some favored Scandinavia, often for ideological reasons later adopted by Nazi Germany. Others cited linguistic traits in the Baltic or archaeological patterns near the Danube.

By the 1960s, attention turned to the Pontic–Caspian Steppe, north of the Black and Caspian Seas. Spinney and Mallory support this theory, which is backed by genetic research published in Nature in 2015.

The studies analyzed ancient DNA from burial sites linked to the Yamnaya culture, revealing that steppe populations spread east to Asia and west to Europe around 5,000 years ago. These migrants replaced up to 90% of the gene pool in parts of Europe.

Spinney notes that most European men today, and millions in Asia, carry Y chromosomes from these steppe ancestors. No other migration, war, or pandemic left a comparable impact on genetics, culture, or language.

Mallory calls it remarkable that people in Iceland, India, and Greece speak languages that once stemmed from a single system. But the Yamnaya’s own language remains unknown, lost without a trace.

While Indo-European languages dominate, Gibb reminds readers of the many voices at risk of disappearing. In Rare Tongues, she explores why some languages vanish while others survive. Namibia, for instance, adopted English as its sole official language after gaining independence in 1990.

Although English was spoken by less than 1% of the population at the time, it was chosen to avoid favoring any particular Indigenous group. However, over three decades later, only about 3.4% of Namibians speak English fluently, partly due to a shortage of qualified teachers.

Gibb warns that such policies can threaten native languages. In Australia, 93% of Indigenous languages are extinct or endangered. In India, that number has increased from 196 to around 600 in just over a decade, according to UNESCO.

Language loss also risks erasing traditional knowledge. A study across the Amazon, North America, and New Guinea found that 75% of more than 12,000 plants had names in only one local language. Many of these plants were used to treat heart disease, mental health issues, and pregnancy complications. Without the language, the knowledge fades, even if the plants remain.

But it is not all bad news, because some languages are finding new life. Manchu is taught in Chinese universities. Māori became an official language in New Zealand in 1987. Gaelic gained status in Scotland in 2005 and now appears on public signage. Even whistled languages, used in mountainous regions to communicate over long distances, are being studied and preserved.