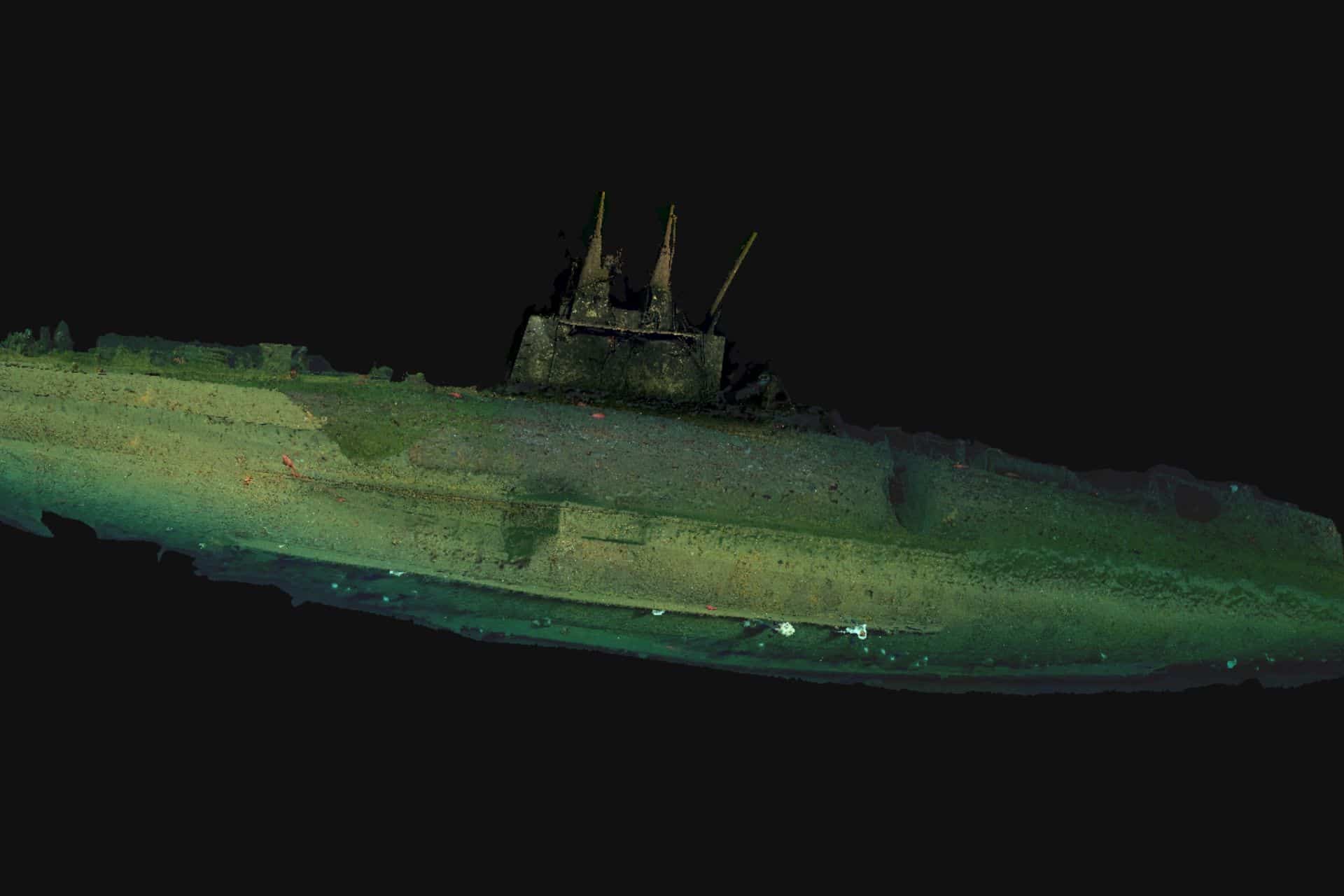

Researchers have released the first clear images of the USS F-1 wreck, a US Navy submarine lost in a tragic accident during the WWI era. The submarine sank on Dec. 17, 1917, following a collision during exercises, claiming the lives of 19 crew members. Its wreckage now rests over 1,300 feet beneath the ocean surface off the California coast.

The images were captured during a deep-sea expedition led by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) between Feb. 24 and March 4. Using the human-occupied submersible Alvin and the autonomous underwater vehicle Sentry, the team documented the site in unprecedented detail.

The mission was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), along with the Office of Naval Research (ONR), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC).

The primary objective of the cruise was to test Alvin and Sentry’s new systems and engineering functions. However, the mission also served as a training opportunity for new pilots and provided a chance to explore historically significant underwater sites.

“Advanced ocean technology and simple teamwork played a big part in delivering these new images,” said Bruce Strickrott, senior pilot of Alvin and manager of the Alvin Group at WHOI.

“Once we identified the wreck and determined it was safe to dive, we were able to capture never-before-seen perspectives of the sub. As a U.S. Navy veteran, it was a profound honor to visit the wreck of the F-1 with our ONR and NHHC colleagues aboard Alvin.”

During the expedition, researchers also surveyed a nearby Navy torpedo bomber that crashed in 1950. Using sonar mapping tools aboard the Atlantis research vessel and Sentry, the team created detailed images of both wrecks.

Still and video footage from Alvin’s cameras were later used to develop high-resolution 3D photogrammetric models of the submarine and the seafloor.

For Brad Krueger, an underwater archaeologist with NHHC, the dive marked his first trip aboard Alvin—and his first visit to a historic wreck in person.

“It was an incredibly exciting and humbling experience to visit these historically significant wrecks and to honor the sacrifice of these brave American Sailors,” Krueger said.

Rob Sparrock, an ONR program officer and fellow Navy veteran, described the nearly eight-hour dive as a solemn privilege. “It also reminded me of the importance of these training dives, which leverage the knowledge from past dives, lessons learned, and sound engineering,” he said.

Following the dives, the crew aboard Atlantis held a remembrance ceremony above the wreck site. A bell rang 19 times—once for each sailor lost in the 1917 accident.

“History and archaeology are all about people and we felt it was important to read their names aloud,” said Krueger. “The Navy has a solemn responsibility to ensure the legacies of its lost Sailors are remembered.”

Anna Michel, chief scientist for the National Deep Submergence Facility and mission co-leader, emphasized the care taken during the operation. “While these depths were well within the dive capability for Alvin and Sentry, they were technical dives requiring specialized expertise and equipment,” Michel said.

The data and models collected during the expedition will support future deep-sea research and contribute to ongoing efforts to document and protect U.S. Navy heritage sites.