Long before the fiery pits and pitchforks of Christian Hell haunted the religious imagination, the afterlife in ancient Hebrew thought was a muted, shadowy place known as Sheol.

In early Hebrew belief Sheol was not a realm of torture or glory but a land of forgetfulness—where all the dead, both righteous and wicked, shared a common fate. In many ways, Sheol resembled the Greek Hades—not in its geography or grandeur but in its indifferent stillness for humans. It was a silent cavern of shadows, where even the most luminous of biblical figures—Adam, Moses, David—drifted as insubstantial shades, unseeing and unfeeling.

This early view of the afterlife was stark in its impartiality. There was no moral calculus at work. Like Hades, which offered only a few exceptions like the Elysian Fields for heroic souls and Tartarus for divine rebels, Sheol was not a realm of judgment. Tartarus in Greek cosmology was the abyss reserved for beings and demigods which had disrupted cosmic order—Cronus and the Titans, Sisyphus, Tantalus, etc. Similarly, in early Jewish thought, the concept of eternal punishment was not for humans but reserved for cosmic transgressors. The fallen angels, Watchers, and eventually, Satan himself were among these transgressors. Human beings would end up into Sheol, regardless of virtue.

Everything began to shift during the Second Temple era, especially after the Babylonian exile. Exposure to Persian and Babylonian cosmologies brought with it a dualistic lens—light versus darkness, reward versus punishment, and a more layered concept of the soul’s journey after death. The once-shadowy Sheol began to split.

By the time we reach texts like the Book of Enoch and later 2 Maccabees, we find something new: consciousness after death. Some souls now appear to experience joy and closeness to the righteous forefathers—in the “bosom of Abraham“—while others suffer for their moral failings. The idea of resurrection, known as the time when the dead rise, are judged, and receive either eternal reward or damnation also enters the scene. Sheol was no longer neutral ground; it had become a moral landscape.

Into this evolving spiritual world steps Jesus of Nazareth, whose teachings reflect and further shape these Second Temple ideas. In the Gospels, Gehenna becomes the word most commonly translated as “Hell.” However, Gehenna was not a metaphysical realm. It was a real valley outside Jerusalem, once a site of child sacrifice and later a cursed landfill.

Jesus used it to describe the fate of the eternally damned who never repented after resurrection. He evoked Hell to stir moral urgency, often in parables, and talked about the rich man and Lazarus and how he was punished in the outer darkness. He spoke of the weeping and gnashing of teeth—images heavy with consequence. The rich man is punished and wants to warn his own people about the reality of eternal damnation.

The apocalyptic dimension deepens in the Harrowing of Hell, the moment between Christ’s death and resurrection. Though not described in the canonical Gospels, it is elaborated on in early Christian tradition and Byzantine hymnography, wherein Jesus descends into Sheol (or Hades), breaks open its gates, and raises Adam and the righteous dead. In iconography, Christ pulls Adam and Eve from their tombs, crushing the gates of Hell underfoot. This is a triumphant, cosmic jailbreak.

St. John Chrysostom, one of the most influential Church Fathers, offers vivid and unequivocal teachings on the reality and nature of Hell. He emphasizes that Hell is not a metaphor but a tangible, eternal punishment for the unrepentant.

Chrysostom describes Hell as:

“A sea of fire—not a sea of the kind or dimensions we know here, but much larger and fiercer, with waves made of fire, fire of a strange and fearsome kind.”

He further elaborates on the eternal nature of this punishment:

“For that it has no end Christ indeed declared when he said, ‘Their fire shall not be quenched, and their worm shall not die.’”

Chrysostom’s vivid imagery and firm stance underscore the seriousness with which early Christian theology regarded the concept of Hell.

Chrysostom even acknowledged that the idea of posthumous justice was not exclusive to Christian doctrine but resonated across human thought and culture. “Even poets, philosophers, and writers,” he writes, “have contemplated future retribution and spoken of the punishments that exist in Hades.”

While their accounts lacked precision and were shaped by distorted echoes of Christian truths, they nonetheless glimpsed the concept of divine judgment. He references vivid imagery from Greek mythology and speaks of rivers such as Cocytus and fiery Phlegethon, the water of Styx, and Tartarus buried deep beneath the earth. Chrysostom saw these as symbolic reflections of a real and terrible judgment.

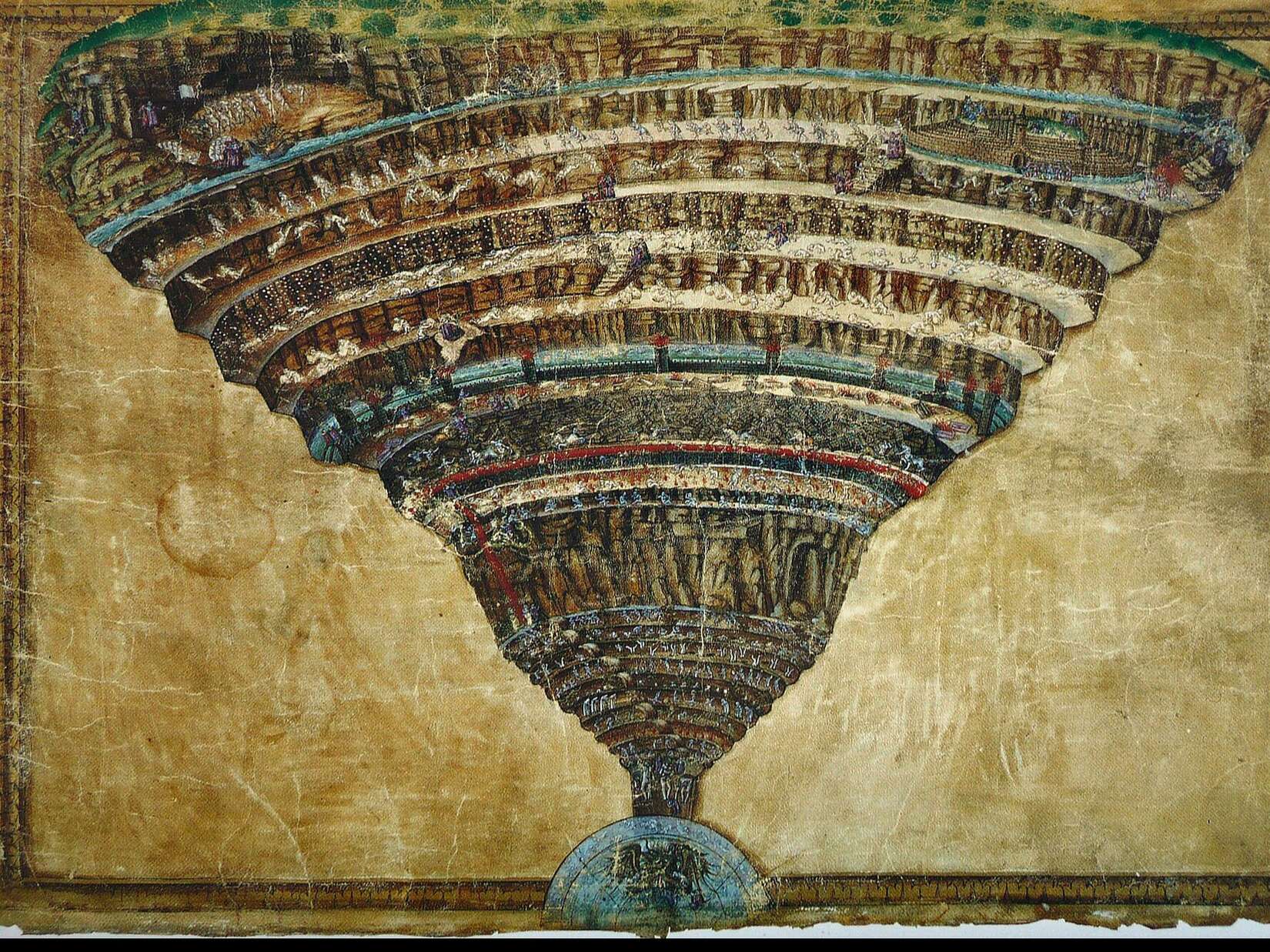

Yet for all this theological richness, the modern Western conception of Hell owes just as much to poetry as to scripture. Dante Alighieri’s Inferno crystalized an image of Hell that has lingered for centuries. This image is an elaborate, layered abyss tailored to specific sins, complete with vivid geography and moral symbolism.

Dante, steeped in classical education, weaves Greek myth into Christian theology. He borrows Virgil as his guide. Virgil, who had described Aeneas’ descent into the Underworld, now leads Dante through the nine circles of Hell. Within these circles, Minos judges the damned while Charon ferries souls across the river of Acheron. Pluto, no longer merely the Greek god of the dead, becomes a guardian of infernal secrets. The punishments of Tartarus, Cerberus, the Furies, and Titanic all reappear—except they now serve a Christian vision of justice.

Dante’s hell is deeply literary, but it codified an emotional and visual grammar of damnation. This shaped sermons, paintings, and imaginations ever since.

The Christian concept of Hell did not begin as fire and brimstone. It began as a quiet, cold shadow—a Sheol where even the best of humanity slumbered without voice or vision. Over time, with the influence of foreign cosmologies and inner theological evolution, Sheol gained color, sound, and flame. It split into places of rest and punishment, opened to the possibility of resurrection, and finally became a moral arena with eternal consequences.

The Christian story made Hell dynamic rather than a mere destination. It was a battleground, where Jesus defeated death itself. And yet, its form continued to evolve, shaped not just by theologians and saints, but by poets and painters, preachers and philosophers.