While Uranus was officially discovered as a planet by the astronomer William Herschel in 1781 using a telescope, some ancient Greek astronomers, such as Hipparchus, may have observed Uranus—but only as a fixed star rather than as a planet.

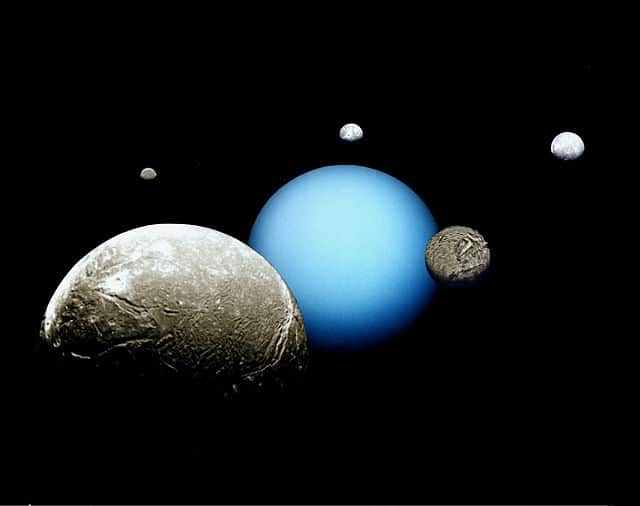

Uranus, the seventh planet from the Sun, is unique in that it is barely visible to the naked eye, appearing as a faint, star-like point in the night sky.

Hipparchus (2nd century BC), among the greatest ancient Greek astronomers, compiled one of the earliest known star catalogs. He meticulously recorded the positions of about 850 stars, significantly advancing observational astronomy. The fact that Uranus was likely observed and recorded by Hipparchus, even if only as a faint star, is a major contribution to the history of astronomy. It is proof of the remarkable precision and thoroughness of ancient astronomers in mapping the night sky.

Because Uranus moves especially slowly across the celestial sphere, its motion was imperceptible to naked-eye observers over short periods. Thus, Hipparchus correctly classified it as a fixed star rather than a planet. From the perspective of ancient Greek astronomy—which was strictly geocentric and based on Earth-centered celestial spheres—this classification was logically consistent. Uranus does not revolve around the Earth in a way that is observable to the naked eye. Therefore, ancient astronomers had no reason to consider it a “wanderer” or planet.

Many ancient Greek astronomers were influenced by philosophers such as Aristotle and astronomers like Hipparchus and, later on, Ptolemy. They identified five planets visible to the naked eye: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Along with the Sun and Moon, these made up the seven classical celestial bodies known as “planets” (meaning “wanderers”).

Uranus, being dim and slow-moving, did not appear among these and was therefore excluded from the traditional geocentric cosmology, which placed Earth at the center, surrounded by the concentric spheres of the other celestial bodies.

Claudius Ptolemy (2nd century AD), the eminent Greco-Roman astronomer and mathematician, authored the Almagest, a comprehensive treatise on astronomy that shaped scientific thought for over a millennium. Ptolemy’s planetary system included the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

Although Ptolemy compiled an extensive star catalog and developed sophisticated mathematical models for planetary motions, there is no mention of Uranus as a planet or wanderer. It likely appeared in his star catalog simply as an unremarkable star without recognition of its planetary nature.

In Greek mythology, Uranus was the primordial sky god, father of the Titans. While the planet got its name from this mythological figure, ancient Greeks did not associate the myth with any observable celestial body beyond the known planets of the time.

The naming of the planet Uranus centuries later reflected a mythological heritage, but ancient astronomy itself made no link between the myth and an actual astral element. The likelihood that Hipparchus observed Uranus as a star highlights the exceptional skill of ancient astronomers in mapping the heavens.

Yet their classification of Uranus as a fixed star rather than a planet was entirely consistent with the contemporary geocentric framework that dominated ancient Greek astronomy. Since Uranus does not visibly orbit Earth, it did not meet the criteria of a “wandering star” or planet from their perspective.

Ptolemy’s Almagest and the classical planetary model included only the five planets visible to the naked eye, omitting Uranus altogether. Ancient Greek astronomers made impressively advanced discoveries for their time. However, the observational technology and conceptual frameworks available to them ultimately limited their progress.

The eventual recognition of Uranus as a planet in the 18th century dramatically expanded the known solar system and challenged the classical view inherited from antiquity.