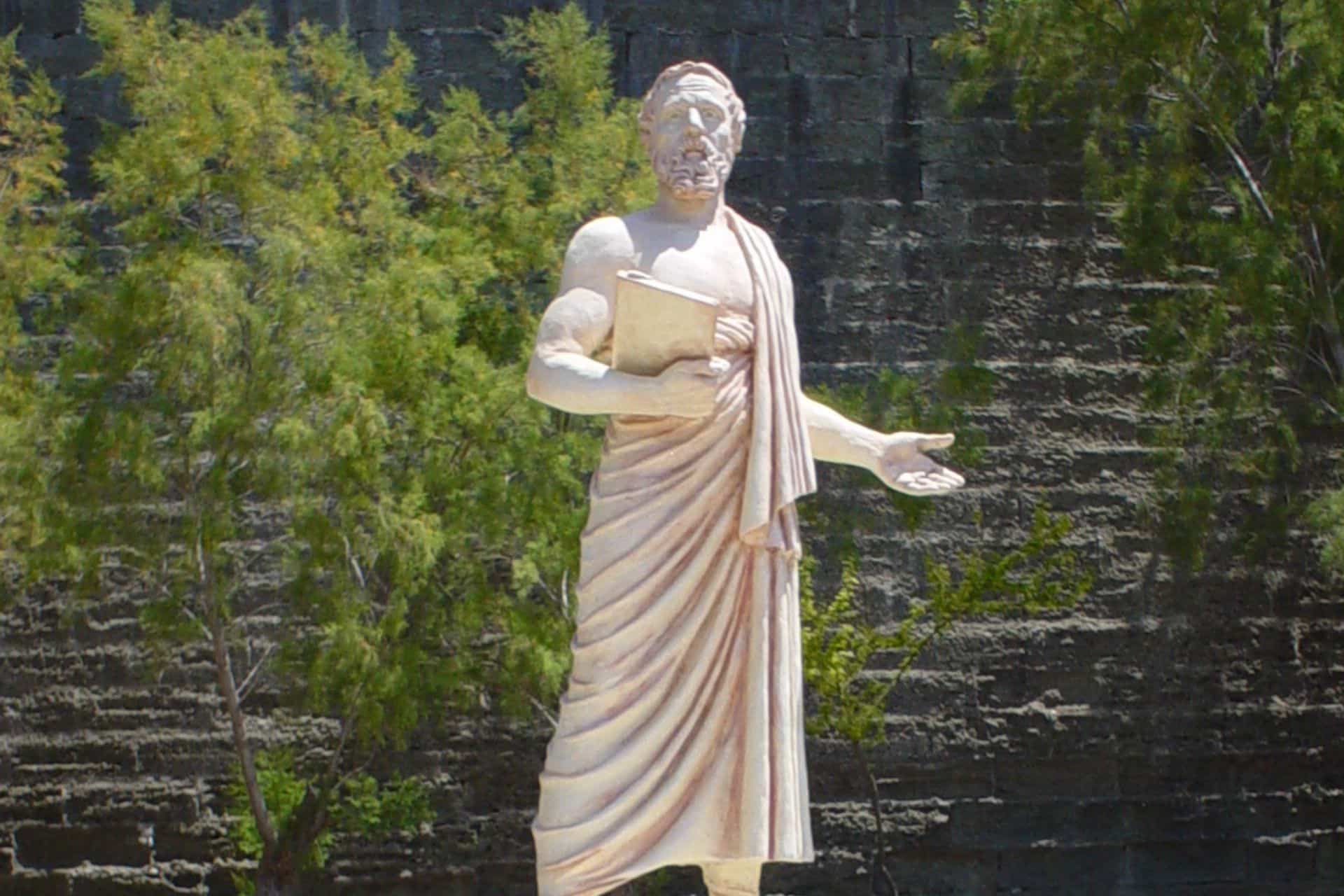

Herodotus of Halicarnassus is often remembered as the “Father of History,” but that title captures only part of his legacy, for he also laid the foundations of what we now recognize as social anthropology and has been regarded as an anthropologist himself.

Beyond chronicling wars and empires, Herodotus engaged deeply with the cultures he encountered. He observed them not as a conqueror or critic but as a curious and reflective outsider.

Herodotus traveled widely across the ancient world, spending extended time among foreign peoples—most notably the Egyptians—not just observing them, but living among them. He spoke with local priests, observed religious rites, and gathered accounts from native informants. This immersive approach resembles the ethnographic methods of modern anthropologists and goes far beyond the detached, second-hand narratives common in his time.

Herodotus took notice of daily practices, marriage laws, funerary customs, diet, and even local gossip. His interest wasn’t limited to kings or generals. Rather, he was drawn to the ordinary fabric of life. This concern with the minutiae of social behavior lies at the heart of anthropological inquiry.

Herodotus is exceptional not only because of the breadth of his travels but also because of his interpretive lens. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he did not assume that Greek customs were inherently superior. He approached foreign beliefs with empathy and curiosity.

In Histories, Book 3, he famously recounts Darius’ testing of Greek and Callatian burial customs. When asked if they would ever adopt each other’s rites, both groups are horrified. Herodotus concludes, “Custom is king of all.” This statement encapsulates his recognition that morality and tradition are culturally embedded.

Rather than denouncing foreign rituals as primitive or irrational, he treated them as meaningful responses to specific historical and environmental conditions. Herodotus described the matrilineal inheritance system in Lycia without ridicule. He explored Egyptian religious festivals with admiration. Furthermore, he catalogued Persian respect for truth-telling with open acknowledgment of its difference from the behavior of the Greeks.

In doing so, Herodotus made a radical choice: he decentered Greece and constructed a world in which no single culture held the moral or rational high ground. This relativist impulse is central to social anthropology today.

Modern social anthropology views myth, religion, and even fantastical stories not as obstacles to truth but as essential cultural artifacts. The question at hand does not pertain to whether something actually happened but what the events reveal about how a group of people make sense of their world.

This was similarly true of Herodotus. He often included supernatural accounts—giant ants in India, gold-digging griffins in Scythia, or divine interventions in battle. However, he rarely endorsed or dismissed these stories outright. Instead, he made reference to them with such phrases as “it is said” or “the locals believe,” signaling that the belief itself was worth recording.

There is a striking parallel to this in the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss, a towering figure in 20th-century anthropology. Lévi-Strauss argued that myth is a kind of language. Its logic is not inferior to science—it is simply structured differently. Myths, he claimed, express fundamental oppositions in human thought: nature vs. culture, life vs. death, order vs. chaos. For him, myths were not childish fictions but powerful frameworks for organizing experience.

Long before structuralism was referred to as such, Herodotus captured this insight intuitively. He did not dismiss a culture’s stories because they defied Greek logic. He documented them as windows into worldview. In this, he was not merely collecting data—he was interpreting human meaning.

Today, social anthropologists study everything from urban legends to creation myths, not to judge their accuracy but to decode their symbolic resonance. Herodotus practiced this long before anthropology officially became an established field. His writing suggests that fantastical stories matter—not because they are factually true but because they are socially true.

Herodotus also used cross-cultural comparison to reveal patterns. He didn’t simply list facts; he connected them and asked why Scythians embalmed their dead or Egyptians shaved their bodies. His curiosity was analytical rather than sensationalist.

Though he lacked the vocabulary of a modern social anthropologist, Herodotus thought like one. He examined how belief systems interacted with the environment, rituals, kinship, and power and explored how people adapted to geography, how customs regulated behavior, and how memory preserved collective identity.

Herodotus deserves recognition not only as a historian but as the earliest practitioner of social anthropology, as he immersed himself in foreign worlds, practiced cultural relativism, and treated myths as a meaningful form of cultural expression. He also anticipated methods and attitudes that didn’t become formal academic practice until the 19th and 20th centuries.

Herodotus reminds us that understanding people requires more than data—it requires empathy, patience, and the willingness to listen. In an age of rapid judgment, his work offers a quiet lesson: every culture has its own logic, and it is worth understanding on its own terms.

@epic.echoes8 Herodotus Explore with the help of AI the life and legacy of Herodotus, the Father of History, as he chronicles the ancient world in ‘The Histories.’ Discover his revolutionary approach to documenting the Greco-Persian Wars, cultures, and customs. #ancientgreece #history #ancienthistory #documentary