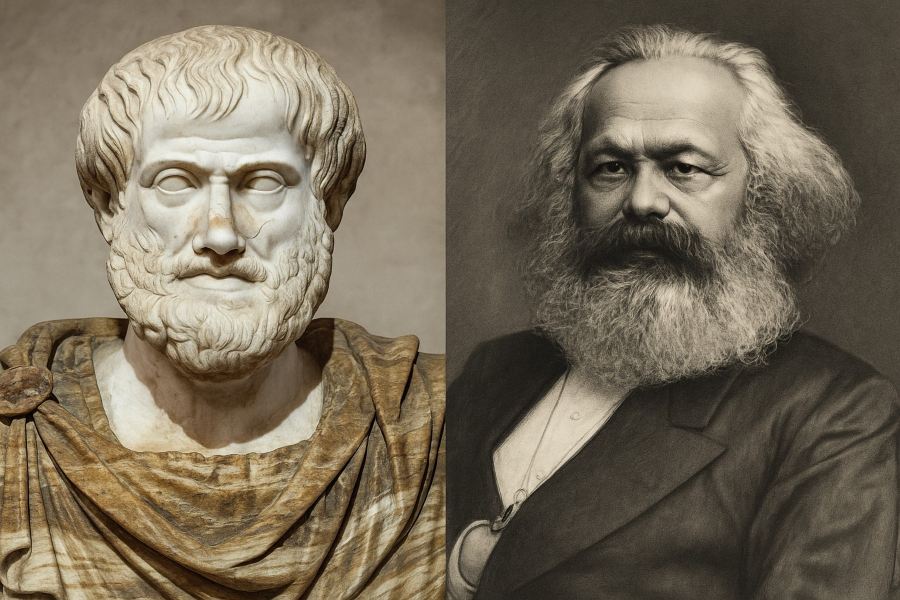

When the philosopher Karl Marx set out to unravel the mysteries of value, exchange, and labor in capitalist society, he found a surprising intellectual ally in Aristotle, the ancient Greek philosopher who lived two millennia earlier. Despite their different historical contexts, both thinkers examined how value arises not inherently from things but from their social relations—especially through the lens of use and exchange.

Marx, in Capital, openly acknowledged Aristotle’s importance. Not only did Aristotle lay the groundwork for distinguishing use-value from exchange-value but his reflections on early human society, property, and the role of labor and technology revealed a conceptual framework that Marx would radicalize for modern critique.

Aristotle’s analysis of value in Politics distinguishes between two uses of a commodity. One is proper and natural while the other is improper or derivative. He writes:

“Every commodity has two uses: both belong to the thing itself, but not in the same manner—one is the proper use, the other is not. For example, a shoe serves either to be worn or to be exchanged; both are uses of the shoe, for he who gives a shoe in exchange to someone who needs it, receiving in return money or food, uses the shoe as a shoe, but not according to its proper use, for it was not made to be exchanged.”

This distinction—between use-value and exchange-value—is a cornerstone of Marx’s analysis. For Marx, this Aristotelian formulation prefigures what he calls the “value-form” of the commodity. Commodities are useful in particular ways (use-value), but also enter into a social system of equivalence when exchanged (exchange-value).

Marx directly builds on this by showing that exchange-value does not exist inherently in an object but arises through the abstraction of labor—because human labor makes different useful things commensurable. Aristotle notes that a shoe does not exist for exchange. Marx took this insight and asked: What kind of society inverts this logic and makes objects valuable only in proportion to their exchangeability rather than their utility?

Aristotle’s theory of the household (oikos) as the first form of society was essential for Marx’s historical materialism. In Politics, Aristotle describes early society as beginning with families. In these families, property was communal and exchange unnecessary. It was only as the population grew and self-sufficiency gave way to interdependence that markets and money emerged.

Marx adopts this trajectory in Capital and his Grundrisse notebooks, writing that commodity exchange is not a timeless activity. Instead, it is a historically specific development that reflects changes in social relations and property forms. The transition from common property to private ownership and from useful production to production for exchange is the material foundation of class society.

In Aristotle, we already see the seeds of this analysis. He distinguishes between natural wealth-getting (production for use) and unnatural chrematistics (the accumulation of wealth for its own sake). Marx seizes upon this distinction to critique capitalism as a system in which the unnatural pursuit of profit replaces human need as the goal of production.

One of the most striking moments in Capital (Vol. I) occurs when Marx discusses machinery and automation. Here, he ironically invokes Aristotle’s dream that if tools could operate themselves, no slaves would be needed:

“If—dreamed Aristotle, the greatest thinker of antiquity—if every tool could perform its task at command or even by anticipation, like the statues of Daedalus that moved of their own accord, or the tripods of Hephaestus that spontaneously began their sacred work, if the shuttles of the loom wove by themselves, then master craftsmen would not need assistants, nor masters slaves.”

This vision did not remain uniquely Aristotelian. Antipatros, a Greek poet from the era of Cicero, hailed the invention of the watermill—the earliest rudimentary form of productive machinery—not simply as a technical advancement but as a social revolution. He praised it as the liberator of enslaved women who had been condemned to grind grain by hand. He envisioned it as the usher of a new golden age of human dignity and freedom.

In these ancient myths and poetic praises, technology is seen not merely as efficiency but as emancipation. The ancients, despite their slave-based economies, understood that the highest purpose of tools was to free people from servitude.

Marx, however, saw this ancient hope turned upside down in modern capitalist society. In his words, what was supposed to free labor had become its jailer:

“Ah, those idolaters! They knew nothing of political economy or Christianity, as discovered by clever Bastiat and even cleverer McCulloch. They failed to understand, among other things, that the machine is the most reliable means for lengthening the working day.”

Here, Marx mocks the liberal economists of his time. Frédéric Bastiat and John Ramsay McCulloch, champions of laissez-faire capitalism, celebrated mechanization without recognizing its role in intensifying exploitation. Unlike the “idol-worshiping pagans,” who at least had the imagination to conceive of automation as a force for liberation, these modern theorists lacked even that mythical foresight.

Marx continues with biting irony:

“They failed to understand, among other things, that the machine is the most reliable means for lengthening the working day.

Thus the strange phenomenon arises in the history of modern industry. That the machine, the most powerful instrument for reducing labor time, becomes the most unfailing means of converting the whole life of the worker and his family into labor-time for capital’s valorization.”

The true paradox for Marx is that mechanization offers a means to liberate humanity but capital instead weaponizes it to intensify exploitation. The ancients envisioned automation as a means of human emancipation. Capitalism uses it to deepen alienation and dependency.

The irony is profound: the ancients dreamed of freedom through the machine, and capitalism delivered machines that reinforce dependency. In this way, Marx reclaims the ancient vision but also shows how the promise of automation has been betrayed.

Marx’s dialogue with Aristotle was not just academic—it was dialectical. He admired Aristotle’s clarity in distinguishing between types of value and his historical insight into the development of exchange. However, Marx also showed how the slave economy of antiquity historically constrained Aristotle’s ideas.

Ironically, in an age in which full automatism is increasingly possible, the prevailing economic model continues to reproduce the conditions that Aristotle associated with slavery—not through direct ownership of people but through economic compulsion and structural inequality. In that sense, Marx saw in Aristotle both the seed of critical insight and the limit of pre-modern social theory.

Hence, while Aristotle could not imagine that labor determines value in commodities, he sensed something essential: that value is not a thing but a relation and that social forms of labor determine the shape of society itself.