A new study has revealed that a part of northwest China’s Turpan-Hami Basin served as an oasis for plant life during Earth’s worst mass extinction 252 million years ago. The discovery contradicts the long-standing belief that land ecosystems completely collapsed during this catastrophic event.

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences analyzed fossils from the South Taodonggou section of the basin. Their findings, published Thursday in Science Advances, suggest that a stable climate allowed forests and plant life to persist despite the global disaster.

The end of the Permian Period saw the most severe mass extinction in Earth’s history, wiping out more than 80% of marine species. Many scientists attribute the event to massive volcanic eruptions in Siberia, which triggered wildfires, acid rain, toxic gas emissions, and extreme environmental changes. The effect on land ecosystems, however, remains a subject of debate.

Conventional theories suggest that terrestrial ocean life was devastated. However, the new study provides fossil evidence indicating that some regions, such as the Turpan-Hami Basin, escaped the worst impacts.

A new study has revealed that a region of the Turpan-Hami Basin in northwest China was an “oasis of life” for terrestrial plants during a mass extinction event at the end of the Permian Period about 252 million years ago.

The study showed that the overall extinction rate of… pic.twitter.com/14Lds0H3Ux

— China Science (@ChinaScience) March 14, 2025

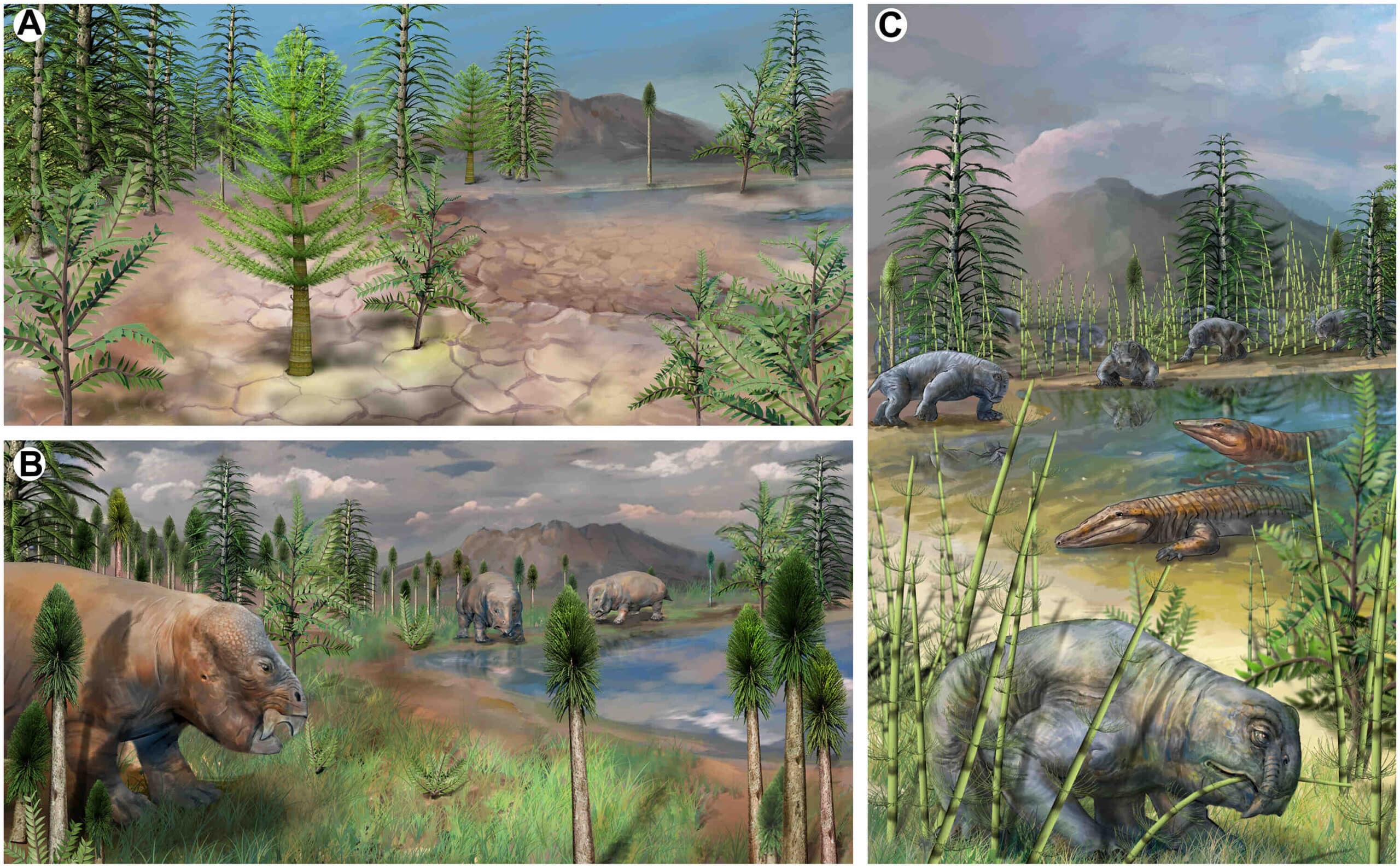

Fossil records from the region show that the extinction rate for spores and pollen—key indicators of plant survival—was about 21%, far lower than the destruction seen in marine life. Researchers uncovered a continuous presence of fern fields and conifer forests spanning at least 320,000 years before, during, and after the extinction event.

This vegetation provided a foundation for ecosystem recovery. Within 75,000 years of the mass extinction, land animals such as Lystrosaurus and chroniosuchians returned to the region. The study suggests that life in the Turpan-Hami Basin rebounded more than ten times faster than in other parts of the world, where recovery was previously estimated to take over a million years.

Scientists attribute the region’s resilience to a semi-humid climate that remained stable throughout the extinction period. Soil analysis indicates that the area received about 1,000 millimeters (39 inches) of rainfall annually, creating a lush environment that supported plant life and migrating animals.

Even though the basin was geographically close to the volcanic activity that triggered the extinction, it remained a refuge for biodiversity. This suggests that certain local climate conditions were critical in sustaining ecosystems when much of the world faced extreme environmental stress.

“This demonstrates that even seemingly perilous locations can harbor vital biodiversity,” noted Wan Mingli, a Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology professor.

“This discovery underscores how local climate and geographic factors can create surprising pockets of resilience, offering hope for conservation efforts amid global environmental changes,” said Liu Feng, another professor at the institute.