Scientists have discovered that oxytocin, often called the “cuddle hormone” or “love hormone” may play a surprising role in delaying pregnancy.

A new study on mice suggests the hormone can slow embryo development, temporarily allowing a mother to pause pregnancy when resources are scarce.

Researchers at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine found that oxytocin helps trigger a natural process called diapause, in which embryos stop growing before implanting in the uterus. This delay may give nursing mothers time to recover before carrying another litter.

Jessica Minder, the study’s lead author and a graduate student at NYU, investigated oxytocin’s role because the hormone is already known to affect nursing and early embryo development.

Diapause is well-documented in over 130 species of mammals, including marsupials like kangaroos and possums, as well as mice and bats. Some scientists believe it may even occur in humans, though the evidence is limited.

Reports from in vitro fertilization (IVF) clinics suggest that, in rare cases, transferred embryos remain inactive for weeks before implantation. In one documented case from 1996, an embryo took five weeks to implant after transfer.

The duration and triggers of diapause remain unclear. Researchers hope further studies will explain how embryos enter and exit this paused state.

To explore oxytocin’s effects, Minder and her team conducted experiments on mice. Female mice that had just given birth were placed with male mice and allowed to mate.

The researchers found that pregnancies in nursing females lasted about a week longer than in non-nursing mice. Since a typical mouse pregnancy lasts only 19 to 21 days, this delay was significant.

Next, researchers used a method called optogenetics, which activates brain cells with light, to stimulate oxytocin release in newly pregnant mice. They timed the stimulation to mimic oxytocin pulses naturally produced during nursing.

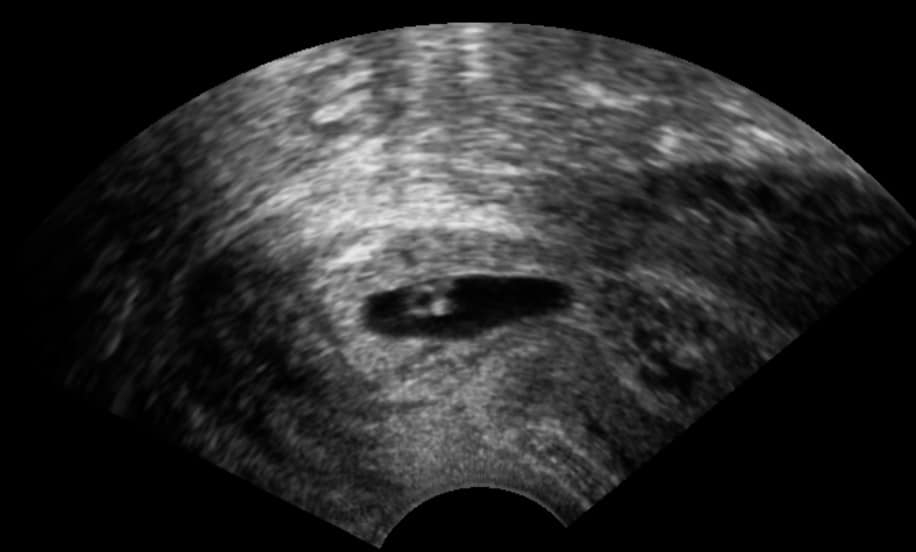

After five days, the team examined the embryos and found that five out of six mice showed signs of diapause. In contrast, mice that did not receive oxytocin stimulation showed normal embryo development.

To confirm their findings, scientists exposed early embryos to oxytocin in lab dishes. These embryos also displayed changes linked to diapause, further supporting the hormone’s role in pausing pregnancy.

While embryos can enter diapause without oxytocin, the hormone appears to help them survive the pause. When researchers blocked oxytocin receptors in mouse embryos, only 11% survived diapause, compared to 42% of embryos with functioning receptors.

Moses Chao, a neuroscientist at NYU said that this study gives us an early look at how embryos manage their energy use. Understanding this process could provide insight into early miscarriages and potential fertility treatments.

Beyond pregnancy, the findings may contribute to broader research on cell survival. In early development, many nerve cells naturally die as the nervous system takes shape, but those that remain can last a lifetime. Chao believes studying diapause could help scientists understand how cells resist stress and survive long-term.

While more research is needed, the discovery that oxytocin influences diapause opens new avenues for studying reproductive health and embryo development. The study was published on March 5 in Science Advances.