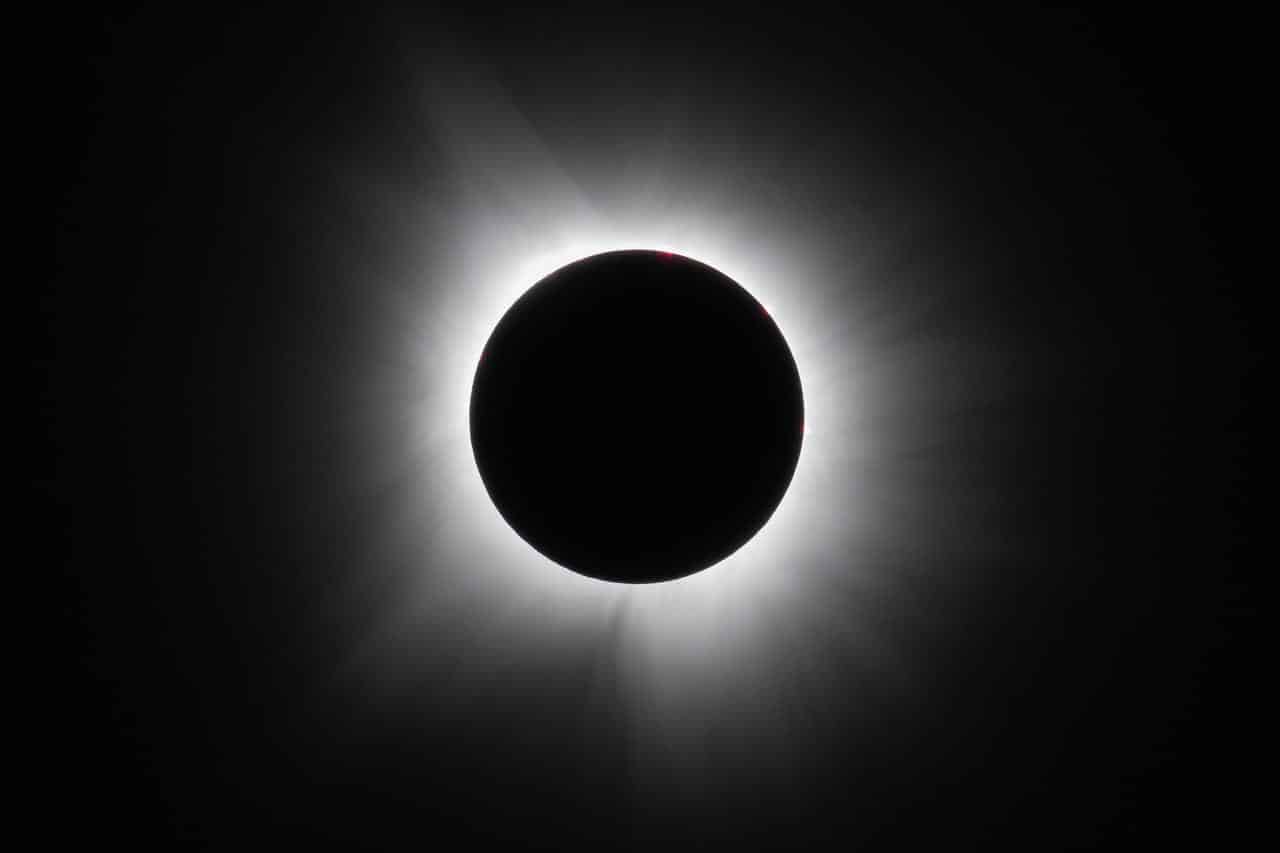

On April 1, 2471 B.C., an unusual darkness fell over ancient Egypt. The sun vanished behind the moon in broad daylight, casting a sudden shadow across the Nile Delta. This rare solar eclipse may have marked more than just a celestial event but also the end of sun worship during the reign of Pharaoh Shepsekaf of Egypt’s Fourth Dynasty.

Giulio Magli, a professor at the Politecnico di Milano and an expert in archaeoastronomy, believes the eclipse’s path coincides with a period when Egyptians started to shift away from sun worship.

“This king precisely corresponds to the eclipse,” Magli told Space.com, noting that the eclipse aligns with Shepsekaf’s rule across multiple historical timelines, despite challenges in dating ancient reigns precisely.

For centuries, the sun played a central role in Egyptian religion. Gods like Horus were tied to it—his right eye symbolizing the sun and strength, his left the moon and healing. By the Fourth Dynasty, worship of the sun god Ra had become dominant.

Pharaohs such as Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure—believed to be Shepsekaf’s father—honored Ra by adding his name to their royal titles and constructing grand pyramids aligned with solar beliefs.

But Shepsekaf broke from tradition. His name lacks the reference to Ra, and his tomb, unlike his predecessors, is not a pyramid. It also doesn’t face Heliopolis, the religious center of the solar cult. Instead, Magli points out that Shepsekaf’s tomb resembles structures found in Buto—coincidentally, the city at the center of the eclipse’s totality.

“No one has been able to explain it, and my idea is that it resembles a building which was in the most sacred place inside the part of totality,” Magli said.

While historians have long noted Shepsekaf’s departure from solar customs, the reason remained unclear. Recent advances in eclipse modeling have helped Magli draw the link. He explained that while calculating the date of an eclipse is simple, pinpointing where its shadow touched Earth is challenging due to tiny, long-term changes in the planet’s rotation.

Ancient Egyptian texts rarely mention eclipses. One of the few references appears on a limestone tablet for Pharaoh Tutankhamen: “I see the darkness during the daylight (that) you have made, illumine me so that I may see you.” Still, no texts directly connect eclipses with omens or fear.

Sun worship would return during the Fifth Dynasty when pharaohs began building “sun temples” alongside their pyramids. Historians debate whether these were newly built or restored structures.

Magli also identified another total eclipse on May 14, 1338 B.C., during the reign of Akhenaten, the 18th Dynasty ruler known for establishing a solar monotheistic religion. The eclipse passed directly over his remote capital.

“It is always difficult to establish if the eclipses were seen in the ancient past as bad omens or good omens,” Magli said.