Long before Newton and Descartes shaped our modern view of science, ancient Greek philosophers were already thinking about the laws that govern the natural world. Contrary to what many scholars believed for decades, new research shows that several ancient Greek philosophers not only described such laws, but they even called them “laws of nature.”

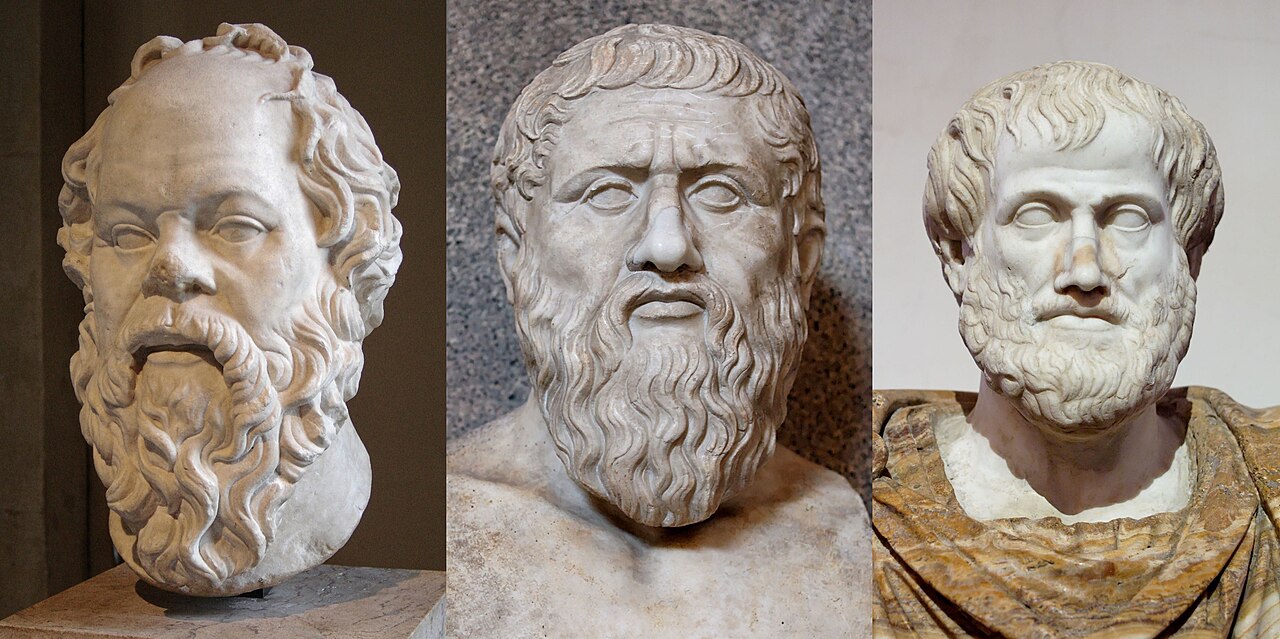

Jacqueline Feke, a philosopher at the University of Waterloo, led a detailed investigation into writings by ancient philosophers, including Plato, Aristotle, Philo of Alexandria, Nicomachus of Gerasa, and Galen. Her study challenges the long-standing belief that the idea of natural laws first emerged in early modern Europe.

Historians often traced the concept of natural laws to Christian philosophers of the 17th century. These laws were seen as decrees of a divine lawgiver, God, acting freely and without limits. This thinking, it was argued, could not have existed in pagan Greek philosophy. But Feke’s findings paint a different picture.

She found that some Greek philosophers clearly used the phrase “laws of nature,” especially in discussions tied to mathematics and medicine. Their works suggest a belief in consistent, universal patterns in nature — the very traits that later became the foundation for modern science.

One of the earliest examples comes from Plato. In his dialogue Timaeus, he links human disease to violations of what he calls the “laws of nature.”

Blood, he explains, must be nourished properly. If it isn’t, harmful substances spread through the body, disrupting its natural balance. In this case, the law of nature is not fixed or unbreakable — it can be violated, leading to illness.

Plato’s student Aristotle also mentions “laws of nature.” He attributes the idea to the Pythagoreans, a group known for their mystical belief in numbers. Aristotle describes how the number three — representing a beginning, middle, and end — was seen as a kind of natural law shaping the universe.

Later philosophers built on these ideas. Philo of Alexandria, a Jewish philosopher influenced by Greek philosophy, wrote that the universe was created in line with unchangeable laws of nature. He described a world shaped not by chance, but by divine reason and order.

Nicomachus of Gerasa, a philosopher from the second century, took the concept even further. His work, ‘Introduction to Arithmetic,’ describes natural laws in mathematical terms.

These laws, he says, govern numbers and the universe itself. He called them “natural” because they were not invented by humans but revealed through reason and observation.

Feke explained that Nicomachus’ laws were mathematical, universal, and necessary — the same qualities that define the scientific laws we know today.

Even the physician Galen, famous for his medical writings, used the term “law of nature.” For him, it described the body’s healthy function. When that natural order was disrupted, disease followed.

Feke’s research suggests that these ideas did not arise in isolation. Many of the philosophers she studied drew from the Platonic and Pythagorean traditions. Both schools of thought saw order and harmony as central to the universe, beliefs that paved the way for thinking in terms of rules or laws.

This rediscovery matters because it shifts our understanding of intellectual history. The belief that nature operates by fixed principles may not have begun with modern science. It may have roots reaching back to the very origins of Western philosophy.

Whether these early ideas directly influenced later scientists like Kepler and Newton remains a question for further study. But Feke’s work makes one thing clear: the ancient Greek philosophers were not strangers to the idea of laws in nature — they were early architects of it.