When you think of medieval princesses, what comes to mind is probably some beauty locked in a tower, waiting around for a prince to show up. Well, Anna Komnene would have rolled her eyes at that stereotype. This 11th-century Byzantine princess had better things to do than wait for rescue—she was busy writing one of history’s most important chronicles!

Born in 1083 to Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, Anna grew up in the heart of the Byzantine Empire during one of its most turbulent periods. Instead of learning needlework like most girls her age, she was reading Homer and studying philosophy. Her parents, surprisingly ahead of their time, decided their daughter deserved a real education, something that was normally reserved for the male offspring. And when we say education, we don’t mean just the basics—we’re talking about advanced studies in history, mathematics, medicine, and literature.

This education paid off in ways nobody could have predicted.

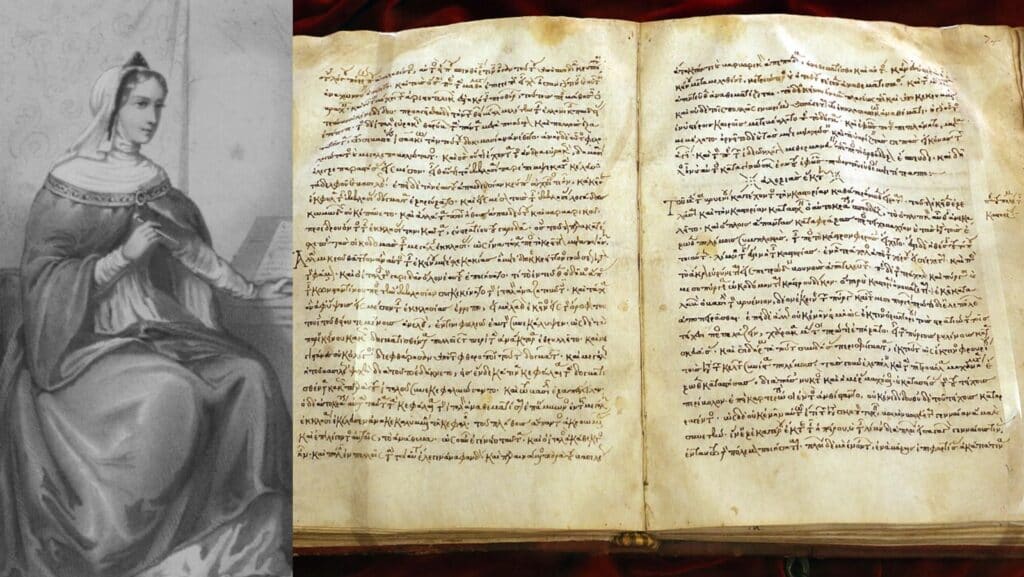

Anna’s masterpiece, the Alexiad, is her marvellous creation that chronicles her father’s reign with the kind of detail that makes historians rub their eyes from tears of joy. She was there for everything: the First Crusade (imagine those rough Western knights showing up at your doorstep), the Norman invasions, the constant political drama and machinations that kept the empire on the verge of falling apart.

Now, let’s be honest, once someone reads her chronicle, it is more than obvious that Anna worshipped her father. Reading the Alexiad, you’d think Alexios could walk on water. But even accounting for her obvious bias, the work is incredibly valuable to us all today. She provides simply unparalleled insights into Byzantine court life, military strategy, and cultural dynamics.

Her descriptions of the Crusaders are particularly entertaining, too. She thought these Western “barbarians” were crude and uncivilized, but she also recognized their military effectiveness and value when it came to battlefields. It’s like getting a sophisticated gossip column about one of history’s most significant events. That’s what her Chronicles feels like to scholars.

What makes Anna truly remarkable isn’t that she wrote a good book—it’s that she dared to write it at all by herself. You see, medieval women weren’t supposed to be historians. They certainly weren’t supposed to have opinions about military campaigns or imperial policy.

Anna didn’t care about “supposed to.”

The Alexiad is bold, confident, and sometimes brutally honest about her era. She criticizes incompetent officials, praises effective leadership, and offers her analysis of complex political situations. It was serious scholarship demanding to be taken seriously, and it worked. The Alexiad became one of the most important sources for understanding this period of Byzantine history. Scholars today still cite her work, debate her interpretations, and marvel at her accomplishments.

Anna Komnene’s life wasn’t all intellectual triumph, though. After her father died, she found herself increasingly sidelined by those in court. She had hoped to see her husband become emperor, but politics didn’t work out in her favor. Writing the Alexiad partly became a way to preserve her family’s legacy and partly a way to assert her own importance in a world that preferred women to remain silent rather than take on the role of a protagonist in the Empire’s political affairs.

It is easy to understand her frustration coming through the text sometimes. Here was this brilliant, educated woman who understood imperial politics better than most of the men making decisions, and she was expected to just… fade into the background after her father passed away.

So, instead of remaining silent, she picked up her pen and made sure her voice would be heard for centuries.

Anna Komnene proved something that seems obvious now but was revolutionary at the time: women could be serious scholars, thoughtful historians, and compelling writers. She opened a door that had been firmly shut and wedged it open for everyone who came after. Every time a woman publishes a memoir, writes a historical analysis, or offers her perspective on current events, she follows the path that Anna Komnene created. Not that Anna gets credit for it—most people have never heard of her. But the precedent she set matters.

The Alexiad remains in print today, nearly 1,000 years later. Students still read it in history classes. Scholars still argue about her interpretations. That’s not bad for someone who was supposed to stay in her (luxurious) room and let the men handle the important issues.

She had something to say, and she said it. In a world that preferred women to stay silent, that was pretty revolutionary.