Hairstyles in Ancient Greece were one of the most significant identifiers of individuals, as they denoted social status and strength. They were also tied to rites of passage and religious rituals.

The hair on one’s head was so particularly valuable to ancient Greeks that it was worthy of its own unique term, being referred to as the kόme (κόμη), and people of the time meticulously cared for it, as they believed it was pivotal to one’s personality and reflected an individual’s social beliefs.

Hairstyles were an essential means of expressing one’s identity. The length and texture—long or short with loose waves or tight curls—was distinctively Greek and contrasted sharply with portrayals of non-Greeks. They were important in that they were a way for people to recognize each other and communicate their place within society.

Hair rituals, such as growing and cutting hair for the purpose of honoring deities, were complex and multi-layered. They needed to account for family status, gender, age, social class, transition points, and cult practices, as well as associations and organizations to which one belonged.

Heroes such as Achilles and Menelaus were portrayed by Homer with blond hair (xanthos), leading many men to lighten their own hair in an effort to resemble them. To do so, they relied on soaps and alkaline bleaches imported from Phoenicia. Some dyed their hair with a mixture of apple-scented yellow flowers and pollen, potassium salts, and even gold powder.

However, in Homeric and Classical Greek, xanthos (Greek: ξανθός) referred to light-colored hair more broadly and did not exclusively mean “blonde” in the modern Northern European sense. Its meaning was more flexible, often encompassing shades like golden, reddish-gold, or light brown.

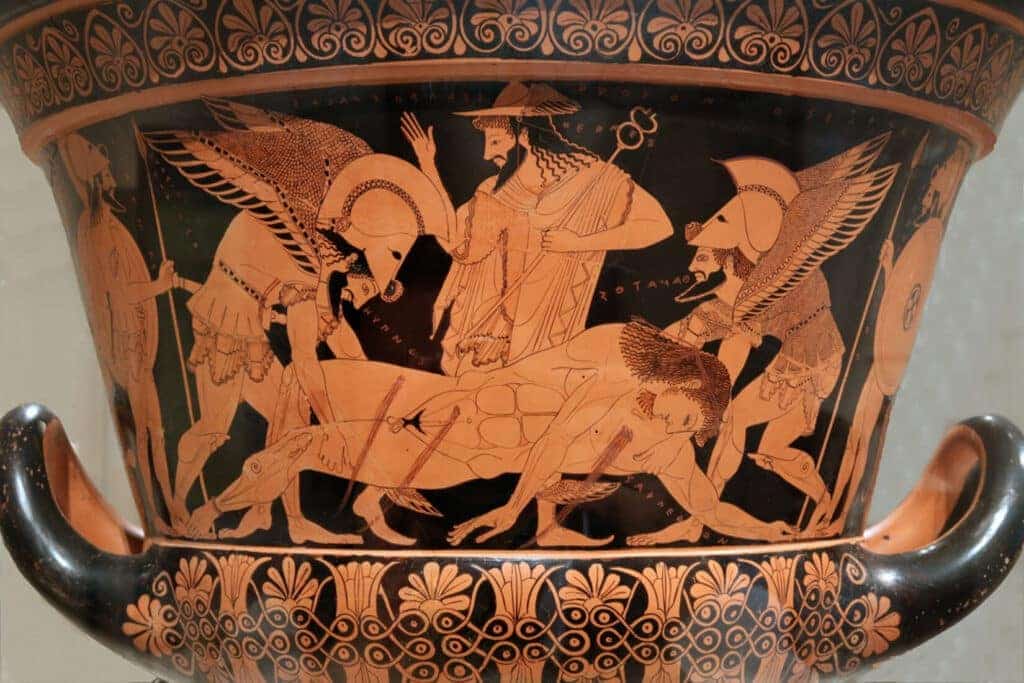

Much of what we know about hairstyles in Ancient Greece stems from depictions of literary works and art, such as sculptures, paintings, amphorae, and other types of vessels. In general, women are nearly always presented with long hair. Slave women, on the other hand, had short hair for hygienic reasons as well as to allow others to socially discriminate between them.

Warriors on amphorae are typically portrayed with pointed beards and long hair while their squires are usually beardless with long, curly hair, and lyre-players have long hair tied back in a bun with a hairband. In a bronze statuette of Apollo, adult men are pictured with beards and somewhat long hair whereas the younger men have no facial hair at all. What marked barbarians, on the other hand, was a moustache with no beard.

Generally speaking, there was a gradual change of style in depictions of men on sculptures and vases from more elaborate to simpler ones. On the other hand, women appeared in works of art donning a variety of ornamental kerchiefs, including pretty bands such as a type of sling known as the “sphendone” (σφενδόνη) due to its shape. A large stamnos, a type of large vase used for serving and storing liquids, depicts groups of women dressed in Ionic and Doric chitons (types of Greek tunics) with various sorts of headdresses.

In literature, the oldest accounts of hairstyles in Ancient Greece are to be found in the works of Homer in which one encounters the dedicating of hair to deities and the dead for the first time ever. This further attests to the importance ancient Greeks placed on hair. In Homer’s Iliad, Book 23, Achilles dedicates his hair to his dead friend Patroclus, for example, in an act that symbolizes his grief for his best friend who has passed away as well as his devotion to their friendship.

Paintings in the palaces and pottery of the Minoan period (c. 3000 and 1100 BC) show dancers with shoulder-length black hair. In Aegean art, men are depicted with single or double plaits, and Homer’s heroes (c. 800 BC) had such hairstyles, as well, as did warriors at the battle of Marathon (490 BC).

The most common hair adornment for women was a type of hairnet or coif made of net work known as a “kekryphalos” in Greek—otherwise also called a caul or “coif of network.” It was worn during the day and at night through to the Classical Period, and Homer made mention of these hairnets, which were frequently made of gold threads or silk, as Pausanias writes.

Overall, during the Archaic Period (c. 1100 to 480 BC), the kouros, the free-standing statues depicting male youth, had long, finely braided, shoulder-length hair at the very least. The maidens (kόre) had numerous braids and oftentimes also donned a coronet. Towards the end of the particular period, women were portrayed with their hair tied back and into a bun, known as the “knidian hairstyle,” named after the Knidian Aphrodite, a statue by Praxiteles of the 4th century BC.

It was in the mid-5th century BC when males began appearing with shorter hair in Greek artwork, and at the beginning of the Classical Period (c. 480 to 323 BC), they were shown with short, neatly trimmed hair. Modern historians attribute the trend towards shorter hairstyles in Ancient Greece to the rising popularity of sports, as athletes had to have their ears free and their hair fixed in place, possibly with hair oil. A good example is the famous Discobolus statue by Myron (c. 460-450 BC).

Alexander the Great’s appearance—clean-shaven (unlike his father) with wind-swept locks combed back from a central part—was a tribute to the importance of youth and was subsequently adopted by other Greek kings. None of his Diadochi appeared with a beard on coinage, statues, or works of art. After Alexander the Great, it became typical for rulers to refrain from having facial hair for several centuries. This was also true of Roman emperors.

In the Archaeological Museum of Amfissa, over eight hundred miniature figurines of 3rd and 2nd century BC females are exhibited. Their hairstyles are particularly interesting, as bronze and golden spirals were used for fastening and decorating the hair. During the Hellenistic period, hairstyles became quite complex, and some of these can be seen on the figurines as well. Knidian hairdressing continued to be especially popular, but from 250 BC onwards, small curls were left hanging unfastened around the nape of the neck.

In archaic times, the ancient Greeks wore their hair long and were thus consistently referred to as long-and-thick-haired Achaeans (Greek: καρηκομόωντες Ἀχαιοί) in Homer’s works. This was a hairstyling practice that was adopted and preserved by the Spartans for centuries.

Plutarch writes that Spartan boys had their hair trimmed quite short. As soon as they reached puberty, however, they let it grow out. The men were particularly proud of their hair, as they deemed it the most affordable of body adornments and consistently took the time to properly care for it prior to going into battle. Both Spartan men and women tied their hair back in a knot over the crown of the head. Brides even shaved their heads and wore men’s costumes as part of the ceremony.

In rival Athens, the boys wore their hair long throughout childhood and had it cut off when they reached puberty. The cutting off of teenager’s hair was a solemn act honored through religious ceremonies. A libation (oinisteria) was initially offered to Hercules, and the hair was dedicated to a deity of choice afterwards. Plutarch writes that Theseus went through the ceremony at Delphi.

Prior to marriage, Delian girls and boys cut their hair in honor of the Hyperborean maidens who died at Delos and laid it on their tombs. A bride would cut her hair on the day of the wedding ceremony as a symbol of submission to her husband and offer it to the goddess Artemis or Athena. She would then pull her remaining her up in a knot. Following the ceremony, the bride wore a crown and special wedding veil. If she happened to be unfaithful to her husband, he would then shave her head, turning her into a social outcast.

The great variety of hairstyles in Ancient Greece makes it difficult to pinpoint the exact period during which each of the hairdos was popular, and there were a number of unique styles as well. Among these was the “melon-like” hairstyle, or the “peponoeidis,” thus named because of what resembled deep parallel grooves akin to those of a melon. Women often left their curls hanging freely around the forehead in the shape of knots or bell clappers in what was known as the “tettix.” Yet another hairdo was the “lambadion,” a type of bun with loose ends which conjured up images of torch flames or horse’s tail.

During the Hellenistic period, hairstyles became more sophisticated and complex. However, the most impressive hairstyle of the time was the knot of Heracles (herakleion amma), associated with good fortune and love. The hair was brushed forward to form a kind of bow or butterfly.

Headbands, diadems, coronets, headscarves, and clips or loops were used in creating the various styles for women, and hair additions and wigs were not uncommon. Garlands of fruit and ivy leaves, mainly from the plant of immortality, the elichryson, which was believed to bring serenity, were also incorporated into hairstyling trends.

Later on, in Roman times, hairstyles became extremely complex and pretentious and were named after the empress or specific woman of nobility who set the trend.