There is a historical anecdote about the reason the Macedonians and Spartans never went to war with each other when Philip and his army conquered all of Greece.

It was 338 BCE when the mighty Macedonian army under King Philip II, father of Alexander the Great, had a triumphant campaign conquering almost all powerful Greek city-states, including Athens.

After defeating the Greek city-states of Athens and Thebes at the Battle of Chaeronea in 337 BCE, Philip II imposed the Treaty of Corinth to create a federation of Greek states known as the League of Corinth (or Hellenic League), with him as the elected hegemon and commander-in-chief.

The league’s purpose was to form a combined military force to campaign against the Persian Achaemenid Empire. Philip’s plan would secure his hegemonic position and fulfill his ambition to conquer Persian lands and expand his power.

While all the other powerful city-states joined the Hellenic League, only one in the lower part of the Peloponnese would not participate: the famous Sparta with its fearless warriors.

Sparta and its allies had fought against Athens and its allies in the Peloponnesian War decades earlier. The Spartans, similar to the Macedonians now, previously fought for the hegemony of the Greek world. They would not bow down to the Macedonians.

When Philip and his invincible Macedonian army marched towards the Spartans, he gave them an ultimatum: “If I attack and if I conquer you, I will show no mercy.”

The brave Lacedaemonians answered with one short, confident, courageous, and daring word, the epitome of laconic language: “If”. A word that left Philip speechless.

The Macedonian king did not attack the Spartans and allowed them to enjoy independence. Historians have provided more than one explanation for his decision. The most reasonable one is that, for Philip, fighting the Spartans would result in significant losses in both men and time. Additionally, Macedonian casualties would damage the reputation of his indomitable army.

There is also the possibility that Philip did not attack Sparta out of respect for their history as gallant warriors and the legacy of the legendary King Leonidas and his heroic battle against the Persians at Thermopylae.

Sparing the Spartans was a clever diplomatic move for the Macedonian king. He demonstrated his magnanimity to the rest of the league members while claiming all the glory for reclaiming the Greek colonies from the Persian conquerors.

King Philip II of Macedon did not have the chance to lead his ambitious campaign to Asia Minor to fight the Persians. In October 336 BCE, one of his seven bodyguards, Pausanias, assassinated him.

After Philip died, Thebes saw the opportunity to rebel against Macedonian dominion. Yet now they had to face the heir to the Macedonian throne whose ambitions were as big as his father’s, and much bigger as it was proven later.

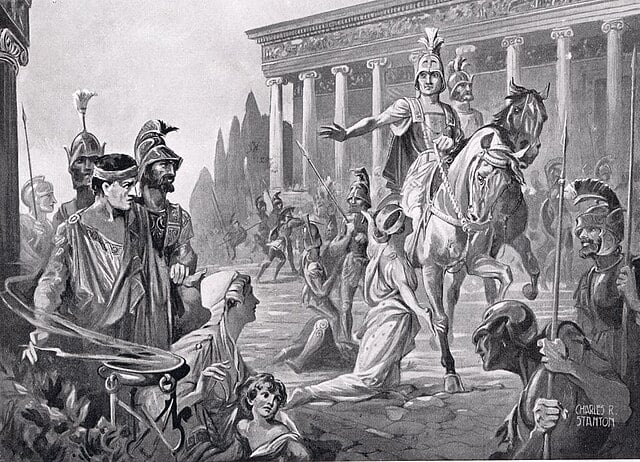

Philip’s son, Alexander, had already fought against the Theban-Athenian alliance in the Battle of Chaeronea next to his father, still a teenager. Now was the time to show his worth and become the great general his father was. He was determined to continue his father’s endeavor. First, he had to suppress the Theban revolt.

He sieged Thebes, but the Thebans showed great resistance. Eventually, his army breached the city and sacked it. Alexander wanted to leave his mark and showed no mercy. According to Diodorus Siculus, he killed 6,000 men and took the remaining Thebans—about 30,000 men, women, and children—into slavery. Then, they razed the city to the ground. Legend has it that he ordered only the house of the poet Pindar to remain intact, as Alexander admired his work.

The young king made an example out of Thebes to show his strength and deter any other city-state that would dare question the Macedonian hegemony.

Alexander began his campaign in Asia Minor in 334 BCE after securing control over Greece and the Balkans. The Persian satraps were familiar with the Macedonians, having successfully repelled an earlier expedition launched by Alexander’s father, Philip. Now, the local Achaemenid satraps marched to confront Alexander on the banks of the Granicus River.

The battle commenced with Alexander initiating a cavalry assault across the river on the Achaemenid left flank. The Persian cavalry unleashed missile fire on the advancing Macedonians, hindering their attack. The beleaguered Macedonians retreated, allowing the Achaemenid cavalry to pursue them down the river.

The Achaemenid cavalry was now vulnerable. Alexander attacked with the rest of his companion cavalry and the entire right wing of the infantry phalanx. As the Macedonians crossed the river, they attacked the Achaemenid troops at close quarters.

Alexander’s men now had the advantage. Their sarissas were far more deadly at such ranges than the shorter Achaemenid javelins. However, as Alexander led his cavalry from the front, he exposed himself to danger.

According to Arrian and Plutarch, Alexander came face-to-face with Mithradates, Darius III’s son-in-law and one of the Achaemenid cavalry commanders. Alexander killed Mithradates by thrusting his sarissa into his face. This exposed him to an attack from the Achaemenid noble Rhosaces, who swung his sword at Alexander’s head. Fortunately, his helmet saved him from harm. Alexander then turned and killed Rhosaces with a thrust of his sarissa into the chest, but was subsequently attacked by Spithridates, the satrap of Ionia and Lydia, from behind. Macedonian commander Cleitus the Black saw Spithridates and killed him before the Persians could approach Alexander.

By now, the Macedonian cavalry had established themselves on the riverbank and were driving the Achaemenids back, who lost their commanders and morale.

This was the first of many victorious battles Alexander the Great fought that eventually forged his vast empire. To underline the significance of the victory, he sent a votive offering of 300 Persian suits of armor to the temple of Athena in Athens. On then he had his men inscribe these words: “Alexander, son of Philip, and the Hellenes except the Lacedaemonians (Spartans) dedicate these spoils, taken from the barbarians inhabiting Asia” (Arrian).

Other than a jab at the Spartans who didn’t want to participate in the Greeks’ campaign to Asia, the words were meant to encourage the rest of the Greeks to join the great expedition to expand the Hellenic world.