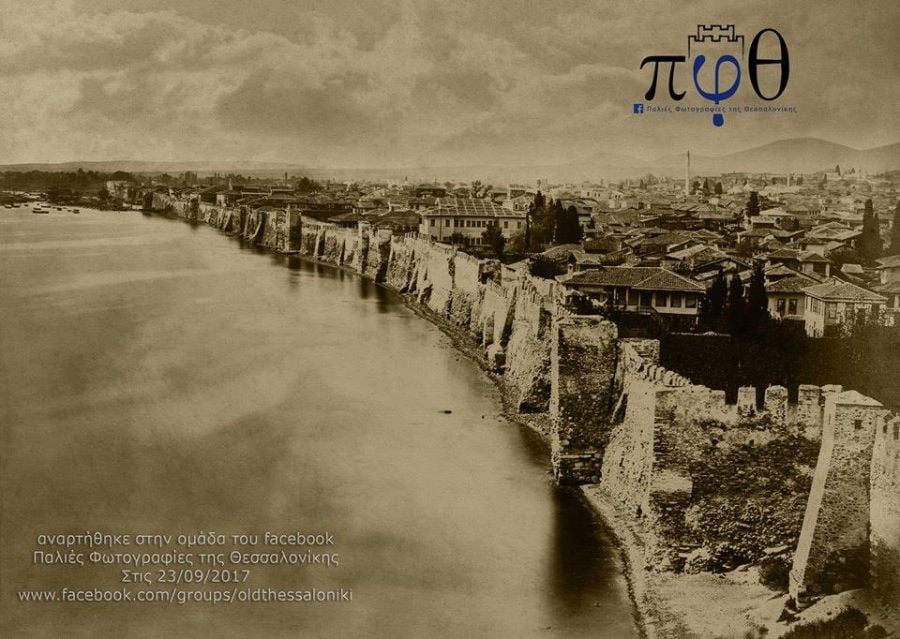

A single image from the 1860s, posted in 2017 in the Facebook group “Old Photos of Thessaloniki,” sent ripples through local history circles and the wider public alike.

The photo, according to its description, depicts Thessaloniki around the year 1860—an unrecognizable version of the city, enclosed by walls that completely block its view of the sea, allegedly taken from the vantage point of the White Tower.

The image—black and white, haunting, historic—has reignited passion for the city’s past and sparked fervent debate. Is it really Thessaloniki? Could this be the earliest photographic record of a city that has seen multiple rebirths?

“This group is a diamond for Facebook and for our city,” wrote one user, echoing widespread admiration for “Old Photos of Thessaloniki,” a community known for meticulous research and remarkable finds.

But this new image, unearthed by group member Zacharias Semertzidis from the Hungarian National Archives, stirred more than just nostalgia. The photo appears in an album labeled “Constantinople” and is attributed to the famed Armenian photography duo, the Abdullah Brothers, active in the Ottoman Empire during the 19th century. The album was exhibited at the 1867 Paris International Exhibition and eventually made its way into the archives of Hungary.

According to the group:

“The first photographic image of the demolished a century and a half ago coastal wall of Ottoman and late Byzantine Thessaloniki is a fact… it has already changed the image and history of the city, to the small extent that a photograph can do so.”

Not everyone is convinced. Prominent historian and curator Evangelos Hekimoglou, a respected authority on the city’s social and geographic history, weighed in via Facebook:

“I examined the photo on the website of the State Archives of Hungary and I express my doubts that it is Thessaloniki, without being able to rule it out at this time. The reasons I invoke are primarily two:

a) There is no trace of Hagia Sophia and the Kara Ali cami’i.

b) We have no other photographs by the Abdullah Brothers from Thessaloniki.”

His measured skepticism has only deepened public interest, inspiring renewed examination of existing urban maps, lithographs, and historical records. Indeed, as Hekimoglou noted, previous visual references to the city’s sea wall are limited to a handful of sketches, none photographic.

The image had quietly resided online since 2017, but it went unnoticed until Semertzidis stumbled upon it amid a digital trove of roughly 10,000 search results for “Szaloniki.” Since being spotlighted by the group, it has become an object of admiration, speculation, and scrutiny.

“It was the feeling of contact with something hitherto unique,” a group admin told Protagon. “But that beginning always includes distrust, doubt, the need for confirmation.”

The photograph doesn’t just challenge what Thessalonians think they know—it disrupts the city’s visual narrative. Before long, the sea wall it may depict would be demolished. By the 1890s, fires and modernization would erase the medieval and Ottoman traces. The Great Fire of 1917 would seal the city’s transformation. The Thessaloniki of today stands on the ashes of multiple iterations, and this image, if real, may be the missing visual link to the one before them all.

The response has been as dynamic as the image itself. “Old Photos of Thessaloniki” continues to host active discussions, fielding contributions from amateur sleuths and seasoned scholars alike. Their collective efforts mirror those of a digital archaeological dig: drawers are opened, albums unearthed, family stories retold.

As one member put it:

“Now the photograph will follow its path… It will be commented on, researched, adorned in important and less important publications, deeply analyzed, abused and certainly exhibited in the coming years.”

True or not, the photograph has already cemented itself in the city’s cultural psyche. Whether it ultimately depicts Thessaloniki in the 1860s—or an entirely different Ottoman city—the conversation it sparked has been profoundly Thessalonian.

Because here, in this city that lives in layers, every image is a story waiting to be rewritten.