A recent study has ended a four-year-long mystery over an ancient Egyptian mummy once believed to be a pregnant woman who died from cancer. The findings reveal that neither pregnancy nor cancer were present and that earlier conclusions were likely the result of misinterpreted embalming materials.

The mummy, widely known as the “Mysterious Lady,” was discovered in Luxor, Egypt – once called Thebes – and brought to the University of Warsaw in 1826. For decades, it remained unexamined until modern technology allowed researchers to take a closer look.

In 2021, scientists from the Warsaw Mummy Project reported that the mummy was not a male priest, as previously thought based on the coffin, but a woman in her 20s.

CT scans suggested she was about seven months pregnant at the time of her death. They also proposed that poor preservation and acid in the womb might have broken down fetal bones, making them invisible on scans. Additional observations pointed to possible signs of cancer in the skull.

However, not all experts agreed with those interpretations. Dr. Sahar Saleem, a radiologist and mummy specialist, publicly questioned the claims, arguing that the scans showed no clear signs of a fetus. She suggested the unusual shapes in the abdomen were likely embalming materials, not a baby.

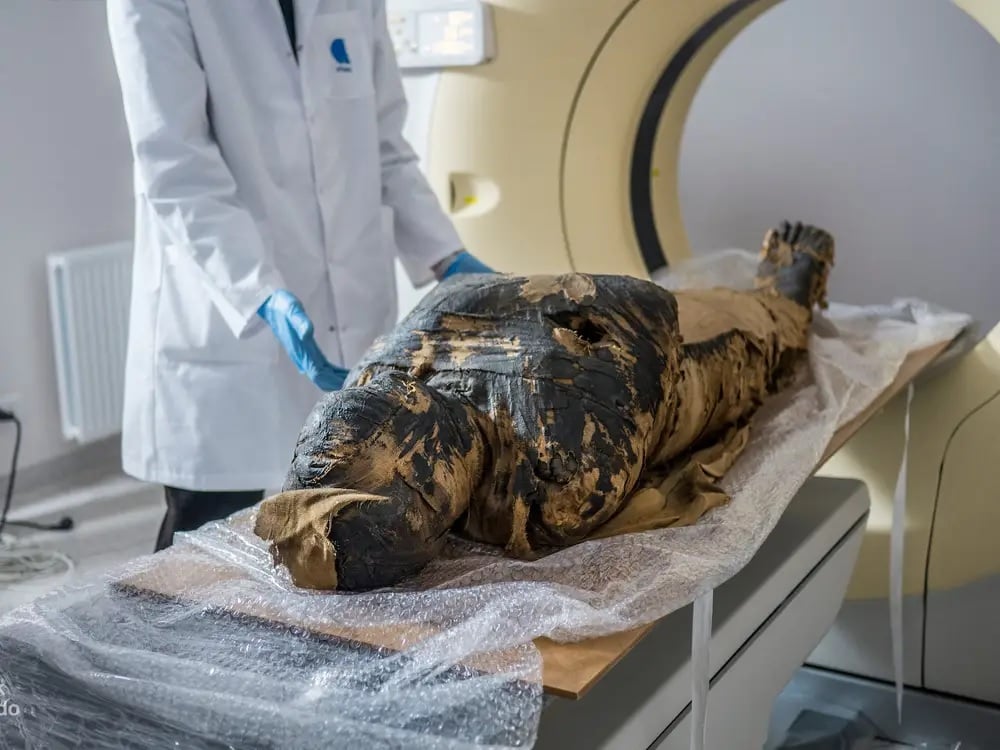

To resolve the controversy, an international team of 14 researchers, led by archaeologist Kamila Braulińska of the University of Warsaw, conducted a detailed reanalysis of the 2015 CT scans. Each member of the team reviewed more than 1,300 scanned images.

Their findings, published in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, were conclusive. All experts agreed there was no fetus inside the mummy.

The bundles previously thought to be a developing baby were identified as materials inserted during the embalming process — a common practice in ancient Egyptian burials.

The study also dismissed the idea that the body became acidic enough to dissolve bones, explaining that the human body’s natural acids are not strong enough to break down bone after embalming.

In addition, the team found no solid evidence of cancer. Damage to the skull once thought to be caused by disease, was instead likely a result of the brain removal process carried out during mummification.

The new research clarifies the misunderstanding and closes the debate. The authors stated, “This should resolve once and for all the discussion of the first alleged case of pregnancy identified inside an ancient Egyptian mummy, as well as the dispute about the presence of nasopharyngeal cancer.”

Despite the corrected findings, public fascination with the so-called “pregnant mummy” remains strong. Researchers suggest that this attention could guide future studies into the lives, health, and care of women and children in ancient Egypt.