Researchers at Ghent University, working alongside artists and archaeologists, have recreated the face and surroundings of a prehistoric woman who lived more than 10,000 years ago in the Meuse Valley. The unveiling took place in Dinant, Namur Province, and the lifelike figure is now set to tour museums across Flanders and Wallonia as part of a traveling exhibition.

The project, which combines science and art, is part of Ghent University’s ROAM initiative. It brings together archaeology, anthropology, genetics, and visual arts to better understand Europe’s early hunter-gatherer societies.

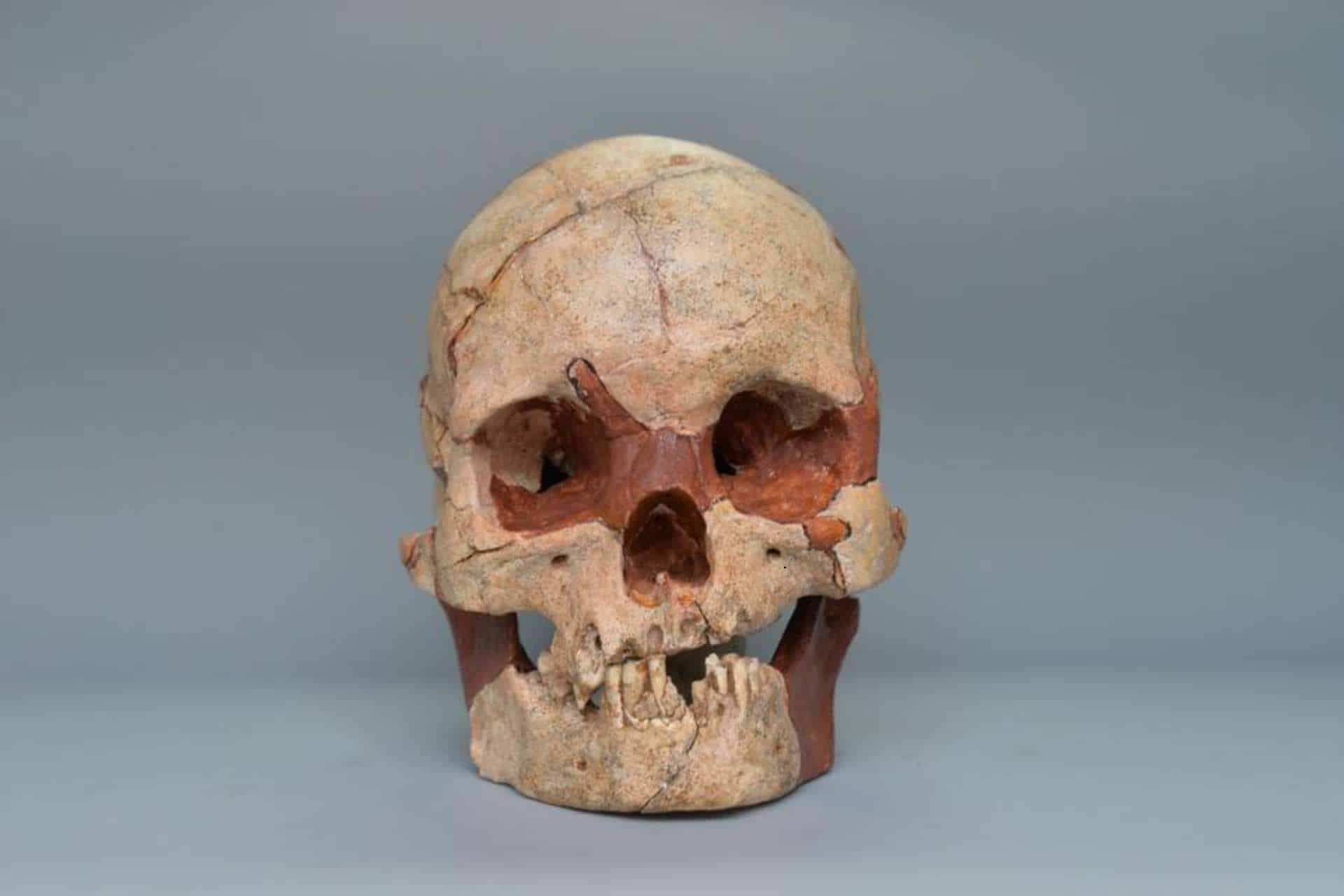

The woman’s remains were discovered in 1988 inside Margaux Cave near Dinant. Genetic analysis later showed that she belonged to a group of Western European hunter-gatherers and shared ancestry with Cheddar Man, a well-known Mesolithic individual from Great Britain. Like him, she had blue eyes. Her skin, however, was slightly lighter than that of many others from the same period.

This is cool: scientists at the University of Ghent, Durham University and other agenies have reconstructed the face of woman whose 10,000 year old skeleton was discovered in a cave near Dinant, Belgium. pic.twitter.com/ziX7OJXy9r

— Vincenzo DM (@DM_Vincenzo) June 16, 2025

“That indicates a greater diversity in skin pigmentation than we previously thought,” said Dr. Maïté Rivollat, lead geneticist on the project, as quoted by Het Nieuwsblad.

Under the direction of artist Ulco Glimmerveen, the team recreated scenes from the woman’s daily life. Campsites, hunting methods, and transportation tools were reconstructed based on archaeological data and scientific models, offering a glimpse into the practical realities of Mesolithic living.

The reconstruction was a collaborative effort between Ghent University, the Walloon Heritage Agency, and Dutch art studio Kennis & Kennis.

Run by twin brothers Adrie and Alfons Kennis, the studio is known for creating realistic reconstructions of extinct humans and animals. Their work plays a key role in connecting modern audiences with ancient history.

To ensure historical accuracy, the team used materials found at Mesolithic sites in the Meuse Valley. Anatomical studies and genetic findings helped guide the appearance of the prehistoric woman’s face, whom researchers have nicknamed the “Margaux woman.”

As part of the public engagement effort, visitors are invited to vote on her official name. The proposed options—Margo, Freyà, and Mos’anne—reflect the region’s cultural and natural environment.

The exhibition, designed for all age groups, highlights both the personal story of the Margaux woman and the broader context of her community. Tools, hunting equipment, and transport methods are on display, revealing the creativity and survival skills of early humans.

By combining scientific research with artistic interpretation, the project offers an accessible and engaging way to connect with Europe’s deep past. The exhibition invites visitors to step into a world that existed thousands of years ago—and see the humanity that links us to it.