Historians often remember Byzantine Emperor Michael III by the unflattering epithet “Michael the Drunkard.”

This is not something that a Byzantine Emperor would want to be remembered for, but that’s the legacy of the man who ruled the Eastern Roman Empire from 842 to 867 AD. His controversial reign still sparks heated debates among historians, as his time in power combined military triumphs, cultural renaissance, and peculiar personal scandals that have left their indelible mark, branding him as Byzantium’s most unconventional ruler.

It has to be noted that some of the things that Michael III is accused of come from historical evidence produced by hostile historians of the succeeding Macedonian dynasty, however, they are worth exploring as they shed light on the way the Byzantine political machine functioned at the time.

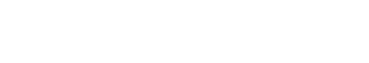

Michael III ascended the Byzantine throne at just two years old, with his mother, Empress Theodora, acting as regent during the years he was a minor. Theodora reigned on behalf of her son at a time when the definitive end of the iconoclastic controversy was cemented, following years of fierce dogmatic debate and clash.

The iconoclastic controversy was a fierce religious conflict that had divided the Byzantine Empire to its core for over a century and had the issue of religious iconography at its heart. By restoring the veneration of icons, Theodora reestablished Orthodox unity, a policy that her son Michael later upheld, bringing much-needed stability to the Empire. However, his path to power took a dramatic turn in 856 when he allied with his uncle Bardas to depose his mother, confining her to a convent -at least, one could argue, she wasn’t murdered as so many other characters or royal courts in medieval Europe.

This was the start of Michael’s journey as a Byzantine Emperor, an era later characterized by significant steps of progress, despite his scandals.

Among the steps in the right direction were reforms that revitalized the Empire’s aging education, the rapid rebuilding of various war-torn cities, which brought jobs and prosperity to these communities, and the resettling of dissident religious groups to stabilize the Empire’s fragile frontiers.

Militarily, Michael III brought about a series of transformative reforms as well. He spearheaded campaigns against the Abbasid Caliphate, recapturing key territories in Cappadocia and Mesopotamia, while his forces famously repelled a Rus’ naval assault on Constantinople in 860. His most crucial and consequential achievement in the front was the Christianization of Bulgaria, a pivotal moment for the broader spread of Christianity in Eastern and Central Europe.

By pressuring Khan Boris I to adopt Christian Orthodox practices in 864, Michael expanded the cultural and religious influence of the Byzantine Empire across the Balkans. Simultaneously, his support for Saints Cyril and Methodius’ mission to Moravia laid the foundations upon which Slavic Christianity evolved.

Nonetheless, Michael’s story as a Byzantine Emperor is equally defined by scandals, intrigue, and turmoil.

The Photian Schism, for example, was a bitter dispute with Pope Nicholas I over the deposition of Patriarch Ignatius, and there were severely fractured relations between Constantinople and Rome.

Michael’s behavior at court grew increasingly erratic, to a point that would create obstacles in the smooth running of the everyday matters of the state. Chroniclers recount his indulgence in alcohol. He was infamously known for his love of drunken revelries, which would often end up in blasphemous behavior like a mockery of religious ceremonies and a tangled personal life that the Church would strongly disapprove of.

This famously involved his wife Eudokia Dekapolitissa and his mistress Eudokia Ingerina, two women who made the situation in his personal life even more controversial. His decision to elevate his charioteer companion, Basil the Macedonian, as co-emperor ultimately proved fatal for him.

Basil, exploiting Michael’s trust and erratic behavior, orchestrated his assassination in 867, seizing the throne and founding the Macedonian dynasty.

However, Michael’s era was successful economically and culturally. Nonetheless, it was equally scandalous and consequential. His court became infamous for its decadent and excessive spending, with the emperor himself often at the center of controversial behavior and choices.

Eyewitness accounts even describe drunken orgies where Michael would mockingly dress up as a priest, performing blasphemous parodies of sacred rituals to the shock -and amusement- of his courtiers, who did not know how to react. He was also known to race chariots through the streets of Constantinople at night, engaging in reckless behavior that endangered both himself and his subjects, a medieval equivalent of drunk driving, one might say.

His personal life was equally tumultuous; he openly showed off his affair with Eudokia Ingerina, even as he arranged her marriage to his friend Basil. He willingly did that to keep her close and continue his extramarital relations with her.

Perhaps most controversially, some historians suggest that Michael may have even had an incestuous relationship with his sister Thekla, though evidence for this claim remains disputed.

These scandalous and erratic behaviors during extreme religious puritanism, combined with his erratic behavior and Basil’s ultimate betrayal, made Michael III’s reputation as one of Byzantium’s most controversial emperors.