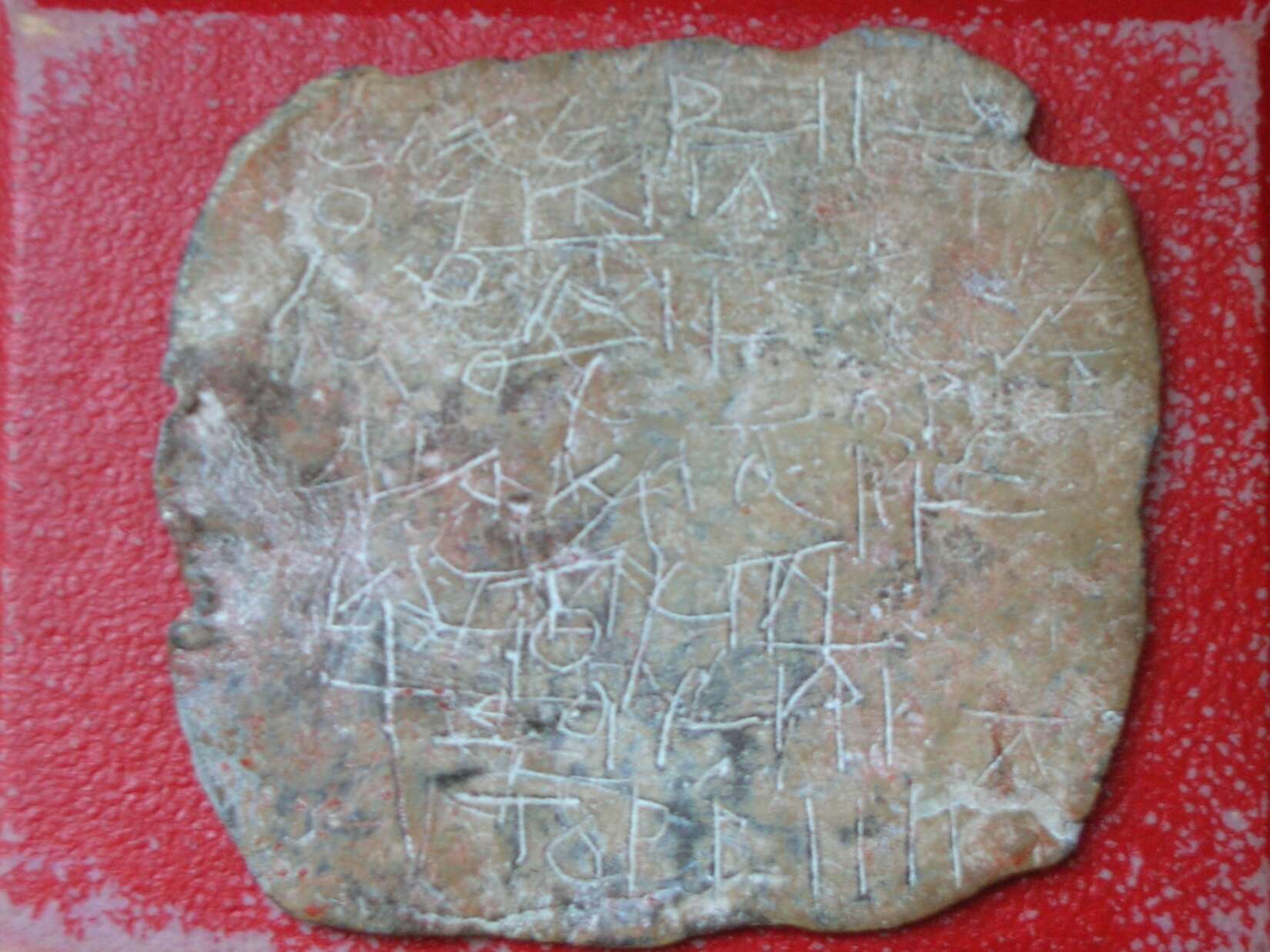

The ancient Greeks deeply believed in the power of curses and their ability to influence the lives of individuals, families, and even entire cities. Curses were considered a direct means of invoking supernatural forces to bring harm upon an enemy. These invocations often took written form, inscribed on lead tablets known as katadesmoi.

Sometimes people spoke them aloud in sacred rituals. Many of these curse tablets have been discovered in tombs, wells and sanctuaries. This suggests a widespread practice rooted in the belief that supernatural powers could be called upon to intervene in mortal affairs.

Curses played a significant role in Greek religious life, particularly in private and legal disputes. Archaeological evidence from sanctuaries like Dodona and temples dedicated to Persephone and Hecate reveal numerous curse tablets. In these, individuals sought divine intervention against rivals, enemies or perceived wrongdoers. Additionally, many of these texts asked the gods to weaken an opponent’s speech, intellect or physical abilities, often in the context of lawsuits or business competition.

One notable example is a 4th-century BCE curse tablet from Athens, in which a man named Polias beseeches the underworld gods to bind his opponent’s tongue and actions in court: “May Hermes and Persephone render him powerless in speech and mind, so that he may be defeated and ruined.”

Greek tragedy frequently explored the devastating power of curses, particularly within the context of familial doom. The House of Atreus, as depicted in Aeschylus’ Oresteia, is one of the most famous examples. There, a cycle of bloodshed and vengeance is perpetuated by an ancestral curse. Similarly, Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex centers on a prophecy and a divine curse. This curse leads Oedipus to fulfill a fate he desperately seeks to avoid.

These plays reflect the Greek notion of curses. Once uttered—whether by gods, ancestors or humans—they could shape the destiny of individuals and entire lineages. The tragedians thus presented curses not only as personal afflictions but as forces that bound human actions to an inescapable fate.

Greek literary and philosophical texts frequently mention curses, reflecting their significance in society. The Greek historian Herodotus records multiple instances where powerful curses affected individuals and entire cities. In one notable example, he recounts how the Spartan king Cleomenes I went mad, supposedly due to the influence of a divine curse. This suggests that even the most powerful figures were not immune to the effects of supernatural retribution.

The Greek poet Euripides frequently explores the destructive consequences of curses in his tragedies. For example, in his play Medea the protagonist invokes dark forces against Jason and his new wife. This sets in motion a catastrophic series of events. Likewise, in his work Hippolytus, Theseus curses his own son, resulting in his tragic death—a narrative that highlights the irreversible and fatal nature of such invocations.

The Irish scholar E.R. Dodds, in his work The Greeks and the Irrational, emphasizes how an overwhelming sense of divine causality shaped Greek society. He argues that the Greeks often viewed misfortune as a result of divine wrath or inherited curses. Similarly, the myth of the House of Atreus shows how an ancient curse creates a cycle of murder and vengeance, passing guilt and punishment through generations (Aeschylus, Oresteia).

The Greek philosopher Plato, in his Laws, acknowledges the power and danger of curses. He explicitly warns against the practice, considering it a source of great evil. He describes how people invoke ancient malevolent powers to harm others, bringing destruction not only upon the cursed but also upon the one who utters the curse.

Furthermore, he suggests that such invocations unleash forces beyond human control. He links them to the interference of demonic entities and chthonic spirits. This perspective reflects the broader Greek concern with the moral and social consequences of invoking supernatural forces for personal gain or revenge.

The practice of writing curses on lead tablets and depositing them in graves or sanctuaries was widespread. Furthermore, archaeological evidence shows that these curses often targeted rivals in legal disputes, lovers who had been unfaithful or business competitors. Meanwhile, the wording of these inscriptions reveals a careful and formulaic approach to invoking divine or demonic intervention.

One well-preserved example from Athens, dating to the 4th century BCE, reads:

“May Hermes and Hecate bind the tongue and mind of Theophilos, so that he is unable to speak against me in court.”

This shows how people used curses pragmatically in everyday life, beyond their dramatic portrayals in myth and tragedy.

Curses played a deeply ingrained role in ancient Greek religious and social life. Whether used in personal conflicts, legal battles or tragic myths, they represented a tangible means of appealing to supernatural justice. From the playwrights who dramatized their devastating effects to philosophers like Plato who warned against their dangers, curses occupied a complex and feared position in Greek thought. Their enduring presence in Greek literature and archaeology highlights the Greeks’ enduring belief in the power of words to shape fate and reality.