Unlike cultures that historically revered their monarchies as near-divine or untouchable figures, Greeks have consistently insisted that their leaders remain grounded, accessible, and subject to scrutiny.

The more one studies Greek history, the clearer it becomes: Greece has always approached politics differently than most nations, whether in the East or the West. Central to this difference is a unique relationship with authority.

Greek attitudes toward leadership stretch back to deep antiquity. During the Mycenaean era (c. 1600–1100 BC), kings—known as wanax—held supreme authority, but they didn’t rule in isolation. Their legitimacy depended on the support of a broader elite, including warriors and nobles.

Rather than acting as divinely sanctioned monarchs, the wanax operated as a primus inter pares—a first among equals—exercising power within a social framework that assigned influence to figures like the lawagetas (military leader) and local chieftains. That is why in the Iliad, Homer’s epic, we see Odysseus frequently questioning Agamemnon’s authority and heroes such as Achilles even swearing at him.

By the time of the Classical period, the idea of a single absolute ruler was not just rejected—it was considered anathema to Greek identity. The polis, or city-state, became the center of Greek political life and with it came a flowering of participatory governance.

In Athens, the cradle of democracy, citizens could directly partake in legislative decisions. The notion of shared rule was paramount. Even when leaders, such as Pericles, rose to prominence, they were not untouchable sovereigns but public servants who could be subject to criticism, challenge, or even ostracism.

This participatory ethos resulted in a cultural expectation: a leader must remain embedded within the people. Any sense of distance—let alone divine elevation—was immediately suspect. Leaders were judged not by their aura but by their proximity to everyday life. They had to speak like the people, live like the people, and act for the people. If they failed to do so, they were seen as tyrants.

Yet even the concept of tyranny in Greece was nuanced. A tyrant, in the ancient Greek sense, was not necessarily brutal. He was simply a ruler who seized power without constitutional legitimacy. Greeks could tolerate—or even admire—tyrants when they served personal or communal interests.

Periander of Corinth was one of the so-called Seven Sages of Greece. He ruled with a heavy hand but earned respect for driving major economic and cultural progress in his city. Similarly, Peisistratus in Athens managed to maintain popular support despite his autocratic grip by promoting festivals and infrastructure projects that benefited the common people.

In southern Italy and Sicily, Italian tyrants such as Dionysius I of Syracuse combined military strength with patronage of the arts and architecture, sometimes begrudgingly winning respect. However, crucially, tyrants were never beyond ridicule, as Greek comedy and satire continuously challenged and mocked their authority.

Greek society cultivated a powerful tradition of comedic satire, which became a fundamental mechanism of political accountability. Aristophanes, for example, the greatest comic playwright of Classical Athens, lampooned politicians, generals, philosophers, and even the gods.

Comedy was a democratic art form, a collective moment when the audience could laugh in the face of power. Countless other satirical poets and performers followed suit in both the Classical and Hellenistic periods, reinforcing the idea that ridicule was not just permitted—it was necessary.

The rhetor Isocrates, in his Panegyricus, famously contrasted the political cultures of Greeks and “barbarians,” stating that, while Greeks can hardly tolerate kingship, barbaric nations cannot live without it. This observation captured a core distinction: Greek culture valued political freedom and shared governance to such an extent that monarchy seemed unnatural and oppressive.

Philip II of Macedon was a figure that many Greeks both admired and deeply mistrusted. While his military genius and diplomatic skill ultimately unified much of Greece under Macedonian hegemony, many city-states viewed him as a threat to their cherished political freedom and autonomy. The orator Demosthenes famously opposed Philip’s growing power. He condemned both the monarchic nature of his rule and the dangers it posed to the traditional city-state governance. Through his passionate speeches known as the “Philippics,” Demosthenes warned Athenians and other Greeks that Philip’s monarchy was antithetical to the Greek ideals of shared governance and civic participation.

Resistance to Macedonian dominance was evident before the decisive Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, where a coalition of Greek city-states, including Athens and Thebes, fought against Philip’s forces. This battle symbolized the climax of Greek efforts to preserve their political autonomy against Macedonian expansion. Even after Philip’s death, during Alexander the Great’s campaign, several Greek cities such as Thebes and Sparta revolted. They feared that the imposition of Macedonian control could end their traditional self-rule. These uprisings demonstrated how deeply Greeks valued city-state independence and actively resisted centralized monarchy.

After Alexander’s death in 323 BC, the tension did not subside. The Lamian War (323–322 BC) was a direct expression of Greek hopes to restore their autonomy by rejecting Macedonian dominance. Greek city-states, including Athens, mounted a rebellion against the Macedonian regency, aiming to reclaim their freedom and political structures. Despite initial successes, the Macedonians ultimately suppressed the revolt, showing that Greeks perceived their monarchy—under Philip, Alexander, or their successors—as an alien imposition incompatible with Greek political culture.

This tradition of irreverence toward power continued through Byzantine and Ottoman times, during which folk culture, shadow theater (such as Karagiozis), and songs preserved the right to laugh at authority. By the time Greece achieved independence in the 19th century, this deeply ingrained political culture stood at odds with the modern European conception of monarchy.

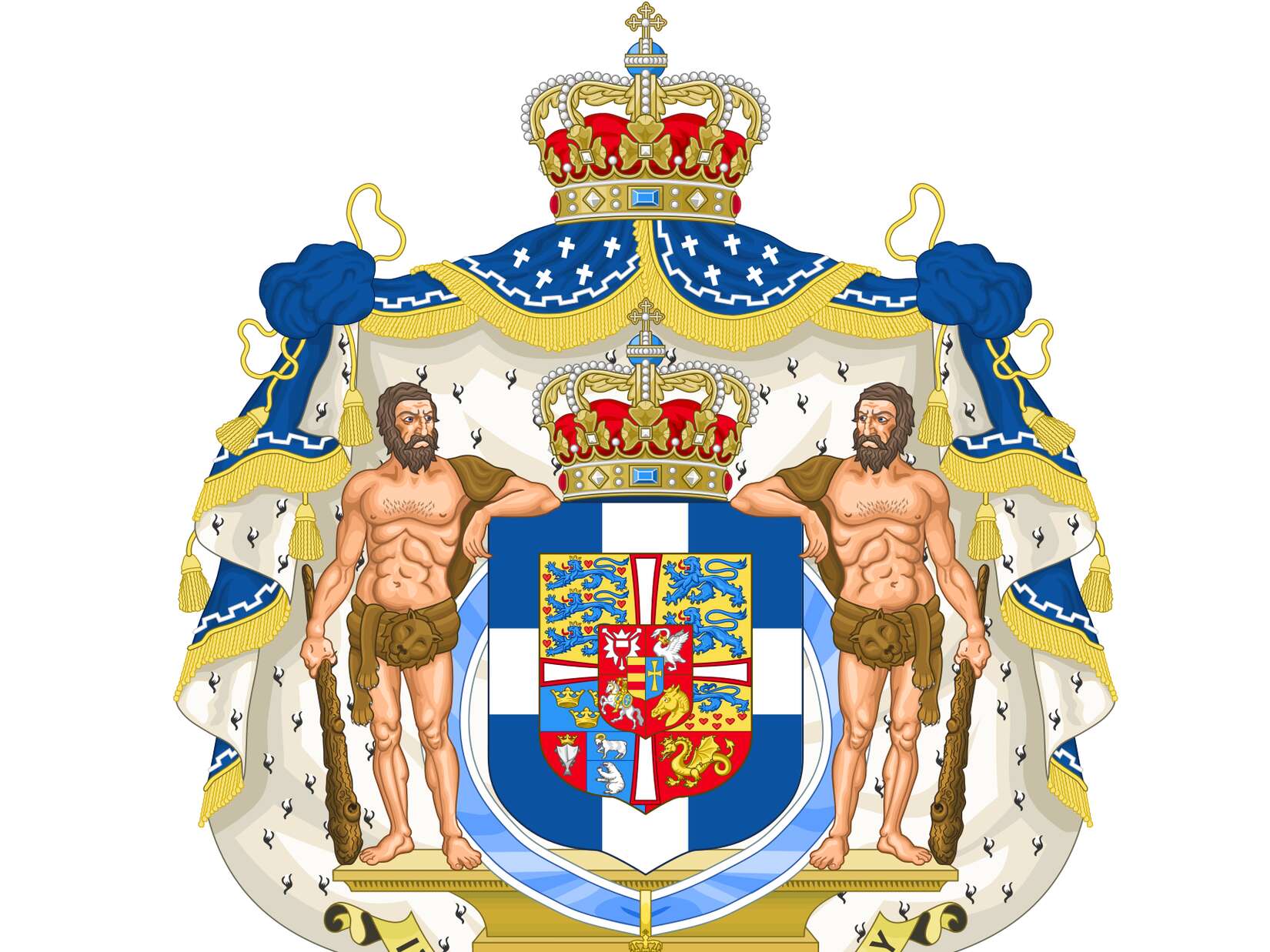

The Greek monarchy, imposed by foreign powers after the War of Independence, was never an organic institution. It was a political transplant, alien to the democratic instincts of the population. Greeks did not grow up with royalty as sacred or untouchable figures. Instead, they expected their rulers to be accountable, human, and serviceable.

Modern Greek history is full of monarchs who failed—not just because they were incompetent or unlucky but because the monarchy itself clashed with the core of Greek political culture. Ioannis Kapodistrias, Greece’s first governor, ruled with an iron fist and paid the price with his life.

The Bavarian prince Otto became king in 1832, but his repeated conflicts with Greek political aspirations led to his exile in 1862. George I was assassinated in 1913, and his successors met similarly turbulent ends. Constantine I’s disastrous handling of the Greco-Turkish War led to his exile in 1922.

At the same time, George II saw the monarchy abolished in 1924, and it took a coup and the strong resilience of the Metaxas fascist dictatorship to restore the monarchy and keep him in power. These cases, along with the 1974 referendum in which the Greek people voted to abolish the monarchy following the fall of the junta, reflect a broader historical pattern: monarchy in Greece failed because it was structurally incompatible with the national character.

This incompatibility of Greek culture with monarchy is further shown in the Greek relationship with political authority more broadly. Greeks change leaders frequently and with little hesitation.

Political change is part of the rhythm of civic life. This is in contrast to countries such as Russia, China, Iran, or Syria, where a change in leadership can signal existential crisis or national trauma. Greeks treat leadership as provisional, often temporary, and always conditional. The frequent turnover reflects not political instability but a deep-seated cultural resistance to the idea of permanent or untouchable authority.

This attitude stands in sharp contrast to many Western monarchical traditions. In Britain, for example, people often revere the king or queen as “otherworldly” figures—removed from the messiness of everyday politics and embraced as symbols of continuity and national identity, not targets for challenge or ridicule.

Even in countries like the United States, where citizens hold presidential elections every four years, people clearly receive political figures differently. Americans actively admire wealthy individuals and have even elected billionaires or celebrities into office. People view wealth as a sign of intelligence, achievement, or leadership potential. Numerous US presidents, including President Trump and others, have gained office partly because voters saw them this way.

In Greece, people generally view politicians with skepticism, questioning both their wealth and motives. Greek politicians often hide their true wealth or go out of their way to appear modest.

This reflects a deep cultural suspicion toward overt success. It also signals the belief that wealth may be likened to corruption or a disconnect from ordinary people. This wariness reinforces the broader Greek tendency to treat political authority as something fundamentally temporary and subject to popular judgment.

Greeks may mock their leaders, accuse them of corruption, or call them useless. However, that never stops them from expecting favors. They vote for them time and time again or engage with the state for personal benefit. Paradoxically, mockery and dependence seem to co-exist. This reveals how Greek political culture prioritizes accessibility and personality over abstract institutional reverence.

The monarchy in Greece didn’t collapse due to a single political mistake or a failed king. It did so because it was never truly accepted by the people. It was viewed as an alien entity; hence, it was rejected. Greeks chose democracy not just as a system but as a cultural expression of their deepest instincts, namely that authority must never stand too far above the people.