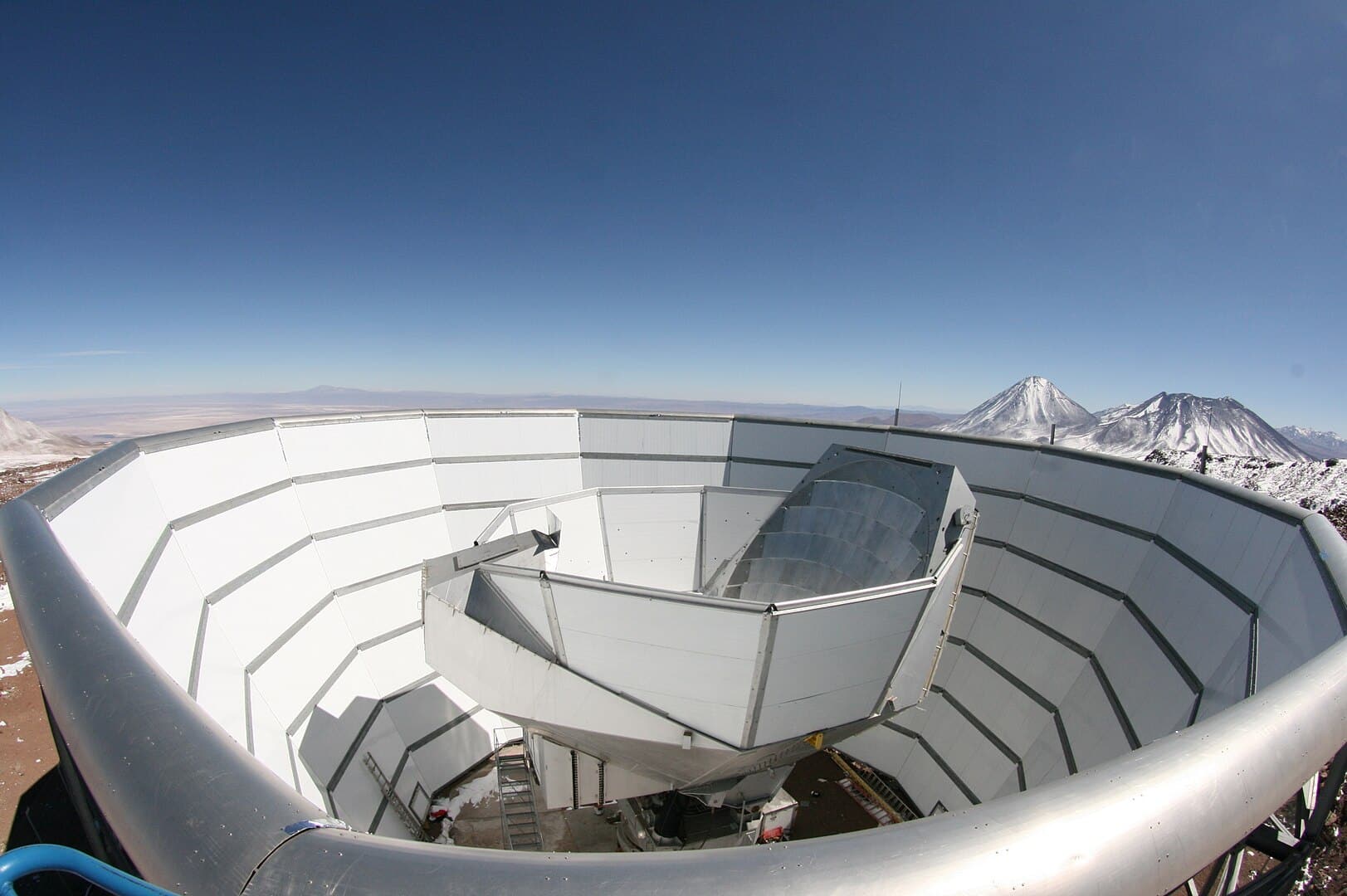

Scientists using the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) have captured the clearest images of the universe’s first light, revealing unprecedented details about its structure and expansion. The telescope, positioned high in the Chilean Andes, recorded light that traveled more than 13 billion years, offering a glimpse of the cosmos when it was just 380,000 years old.

The new findings reinforce key theories about how the universe formed and expanded while addressing long-standing debates about the cosmic growth rate.

The ACT images provide a precise view of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), the faint radiation left over from the Big Bang. Researchers describe it as the universe’s baby picture. Unlike previous observations, these images capture the brightness and polarization of this ancient light, offering new insights into the first structures of the cosmos.

“And we’re not just seeing light and dark, we’re seeing the polarization of light in high resolution. That is a defining factor distinguishing ACT from Planck and other, earlier telescopes,” said Suzanne Staggs, director of ACT and a professor at Princeton University.

The telescope boasts five times the resolution of previous space missions, allowing researchers to detect patterns in the light that were once invisible. These patterns confirm how gravity shaped the early universe, pulling denser regions together, and eventually forming stars and galaxies.

The ACT team has also made the most precise measurement of the universe’s age yet, confirming it to be 13.8 billion years old with an uncertainty of just 0.1%.

Scientists liken the early universe to a vast pond where waves ripple outward. These sound waves, caused by the pull of gravity on cosmic matter, left imprints in the CMB. By measuring these imprints, researchers can determine how fast the universe has expanded since its beginning.

“A younger universe would have had to expand more quickly to reach its current size, and the images we measure would appear to be reaching us from closer by,” said Mark Devlin, an astronomy professor at the University of Pennsylvania. “The apparent extent of ripples in the images would be larger in that case, in the same way that a ruler held closer to your face appears larger than one held at arm’s length.”

The ACT data confirm previous measurements based on the CMB, further solidifying the standard model of cosmology.

The rate at which the universe is expanding, known as the Hubble constant, has been a topic of scientific debate. Different measurement techniques have produced conflicting results. Studies of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) suggest an expansion rate of 67 to 68 kilometers per second per megaparsec. Observations of nearby galaxies indicate a faster rate of 73 to 74 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

ACT scientists have measured the Hubble constant with increased accuracy using their latest data, aligning with the CMB-based estimates.

“We took this entirely new measurement of the sky, giving us an independent check of the cosmological model, and our results show that it holds up,” said Adriaan Duivenvoorden, a research fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics.

To resolve the discrepancy, scientists explored alternative theories, such as changes in the behavior of dark matter and neutrinos or an early phase of accelerated expansion. However, their findings showed no evidence to support these ideas.

“It was slightly surprising to us that we didn’t find even partial evidence to support the higher value,” said Staggs. There were places where we thought the data might point to a solution, but it simply wasn’t there.

ACT, which completed its observations in 2022, has provided a foundation for future studies of the universe’s origins. The data is now publicly available through NASA’s LAMBDA archive, allowing researchers worldwide to analyze the findings further.

Scientists are shifting their focus to the Simons Observatory, a next-generation telescope at the same site in Chile. With advanced technology and improved sensitivity, it aims to refine these measurements even further and continue unraveling the mysteries of the cosmos.

Jo Dunkley, a professor at Princeton University, emphasized the significance of these discoveries.

“By looking back to that time when things were much simpler, we can piece together the story of how our universe evolved to the rich and complex place we find ourselves in today,” she said.