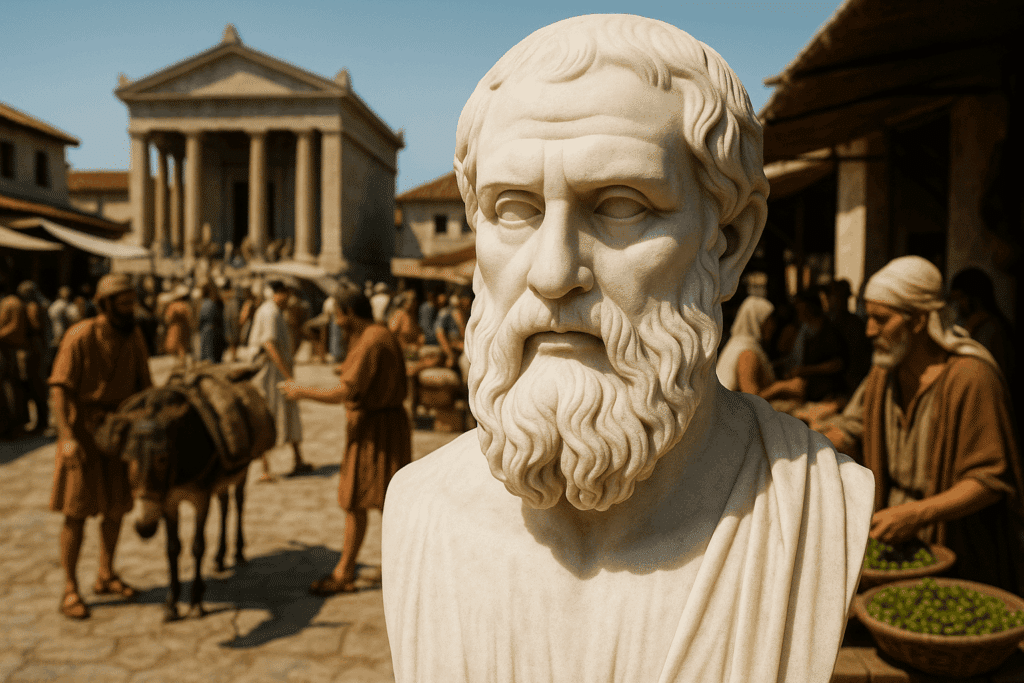

Picture yourself walking through a noisy market square in an ancient Greek town in southern Italy possibly around the year 500 BC, when philosopher Parmenides lived.

It must be a buzzing community, right? The sun is out, donkeys are transporting all sorts of goods, and people are haggling over olives or other products for sale. Everything is moving, shifting, changing. Then this well-respected thinker, Parmenides, wanders over simply to inform you that none of this—not the movement, not the chatter, nor any of the change you see, hear, and feel—is actually happening.

Reality, he insists, is just one solid block of unchanging, eternal things. It does sound completely deranged, doesn’t it? However, this wasn’t just an inane idea. Parmenides dropped a philosophical bomb that sent ripples through Western thought, and these continue to be felt today if you know where to look.

Parmenides lived in Elea (modern Velia), a Greek colony in southern Italy. From what we gather, he must have been a pretty noteworthy character in his city, and there is evidence of his even drafting some of their laws. Unfortunately, all the information we have pertaining to him comes from small quotes preserved by later writers.

Nonetheless, we also have substantial fragments of a poem called “On Nature,” which is Parmenides’ largest surviving body of work. This was written in the style of an epic journey in which the character gets whisked away to meet a goddess who exposes the ultimate Truth (with a capital T).

She draws a sharp line between real reality (the “Way of Truth”) and the messy, confusing world of our senses (the “Way of Opinion”). Parmenides even began a whole philosophical movement based on this, the Eleatics, attracting students the likes of Zeno. You have probably heard of Zeno, the man behind those absolutely fascinating paradoxes about Achilles never catching the tortoise and arrows freezing mid-flight. Zeno was indeed pulling out all the stops to back up his teacher’s mind-bending ideas.

Okay, we know this sounds weird. But what was the earth-shattering secret this goddess shared? When you boil it right down, it comes down to something simple: genuine reality, the stuff Parmenides called ‘What Is,’ exists. It just flat-out is, and there’s no way for it not to be.

On the other hand though, ‘What Is Not’—pure nothing, absolute emptiness—doesn’t exist. You can’t touch it, think it, or really even talk about it properly. It sounds almost like common sense, doesn’t it? Ah, but Parmenides took this seemingly simple idea and, using pure, cold logic, ran with it. If ‘What Is’ truly exists, he figured, it couldn’t have just sprung from nothing (because nothing isn’t there to spring from), nor can it just dissolve into nothing.

Hence, the first conclusion is that reality is eternal. It also can’t change because changing means becoming something different—it would have to involve becoming ‘what it is not’ right now, or gaining some ‘not-ness,’ and we already established that ‘not-ness’ doesn’t exist. In other words, reality has to be unchanging.

If you’re still following, then you should know that Parmenides also argued that reality must be just one single, unified thing. If reality was fragmented, what would separate the pieces? Nothingness? This wouldn’t be possible, so we can conclude that reality is indivisible, a solid whole. But what about movement? To move, you need empty space (nothingness!) to move into. Another impossibility. Therefore, true reality must be perfectly still.

Just let that absurdity sink in. The real world, according to Parmenides’ logic, is this single, unchanging, eternal, motionless blob. A complete contradiction is Heraclitus saying that”everything flows.” Parmenides essentially countered, “Nope, nothing flows, my friend. Trust the logic, your senses are fibbing.”

Right about now, you are probably thinking, “Okay, interesting theory, but my toast did just burn, things do change!” And Parmenides would just calmly file your burnt toast under the “Way of Opinion,” or the unreliable info our senses feed us. It’s incredibly easy to just say that Parmenides was talking rubbish. But that sharp division he carved between the truth you figure out with your brain and the “truth” you see with your eyes? That stuck. That was big.

Plato was practically obsessed with this puzzle. His famous Theory of Forms—the idea of perfect, eternal blueprints for everything—feels a lot like him trying to somehow make sense of Parmenides’ static reality alongside the changing world we live in. And Zeno’s paradoxes? They still pop up everywhere, forcing us to question if motion and division are as straightforward as they seem.

But is any of this ancient Greek head-scratching relevant nowadays to us living in the 21st century? Well, you could argue that it is in certain ways. Some physicists fooling around with ideas from Einstein’s relativity talk about a “block universe” in which past, present, and future all exist together, making our feeling of time flowing just a trick of perception.

Doesn’t that sound vaguely Parmenidean? Or think about basic laws such as the conservation of energy—it can’t be created or destroyed; it can only change form.

This all sort of resembles that old idea that Being can’t come from Non-being. Now, these are just details, not direct lines, but they point to that same deep question with which Parmenides was concerned: is the world we experience the real thing, or is there something far stranger, more unified, maybe even more static, hiding underneath? Science constantly shows us things that defy our everyday intuition, so who tells us that Parmenides wasn’t right after all?